-

It’s common for pregnant women to have some anxieties about childbirth, but how they’ll be treated during labour should not be one of them.

Yet all around the world, an appalling number of women are subject to obstetric violence – the abuse and mistreatment of women during childbirth, including being forced into procedures against their will. In Latin America, it is estimated that around 43 per cent of women will experience this.

Specialist midwives are trained to provide more choices so women can have the delivery they want. Midwives increase safe births and make childbirth a more positive experience, among many other key services.

That’s why UNFPA provided human rights and leadership training to midwives in Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. The course is designed to recognize and strengthen the essential role of midwives in making services equitable and in delivering a high standard of care, free from violence and discrimination.

[Pictured above] Midwife Leonor attends to a pregnant woman during labour in São Paulo. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

“I was hesitant to get pregnant again because the thought of going to hospital scared me,” says Erika, who had experienced obstetric violence with her first child in São Paulo, Brazil.

Her fears were making her reconsider her desire to grow her family.

When she discovered that there were alternatives to delivering in a hospital, Erika became pregnant with her second child, receiving care at a birthing centre.

“Here, they empower a woman in labour to know her own body. It is a more respectful approach, so this gives us a greater confidence,” she says. “The way you deliver a child into the world, a human being, a new life…it’s very important."

[Pictured above] Erika receives acupuncture, a safe and gentle way believed to possibly help turn a baby to the best position for birth, from Leonore at the Casa Angela birthing centre in São Paulo. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

“I want every woman to feel respected in her pregnancy, birth and postpartum care,” says Leonor, who works at the Casa Angela birthing centre in São Paulo, where services are provided exclusively by obstetric specialists.

“Unfortunately, obstetric violence is very common; we hear many reports,” she says. “It hurts the woman not only physically, but also emotionally.”

Leonor believes there is a discriminatory element and that obstetric violence is linked to racism, which studies have confirmed.

[Pictured above] Leonor reviews ultrasound scans. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

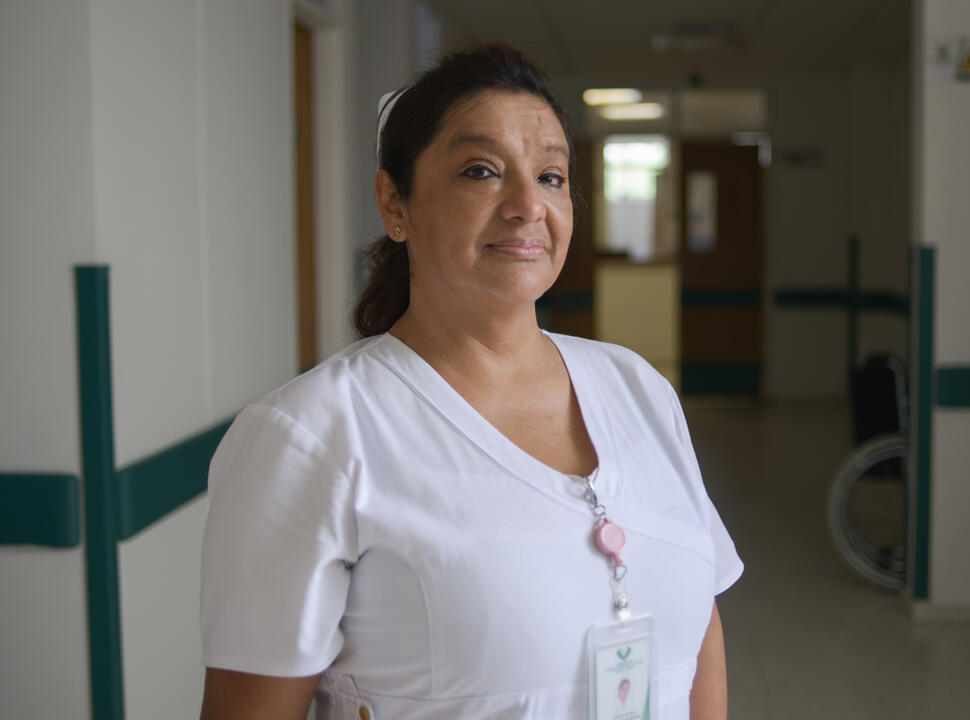

In Tumaco, Colombia, Elisa is head nurse of the delivery room at San Andrés Hospital. She, too, has observed that women who are more likely to face discrimination in daily life are also more adversely affected when it comes to childbirth, including people living in poverty and indigenous women.

“Tumaco is a remote area compared to other parts of Colombia and historically neglected. There is a lot of vulnerability, many social problems,” she says. “Political abandonment has increased the risks for indigenous women.”

“The human rights course is a great learning experience. Midwives have a very important place. It’s important to highly respect and value all women. Birth and care must be human, decent, and it must be intercultural.”

[Pictured above] Elisa says the human rights course is a “great learning experience.” © UNFPA/Carolina Navas

-

The long distances to reach specialist obstetric care from some rural areas means access is not currently equitable, and this can lead to crisis.

“If a woman has complications in our region, she may have to travel for five or six hours in an ambulance,” says Elisa. “We have had maternal deaths where mothers travelled for hours by boat. They arrived totally cold, hypothermic.”

UNFPA is committed to ensuring every woman has access to quality maternal and newborn care, and midwives are at the very heart of this mission. In addition to the human rights and leadership course, we have helped train more than 350,000 midwives to date.

[Pictured above] Elisa leads her team through a training exercise. © UNFPA/Carolina Navas

-

Erika, an intern of reproductive health and midwifery, grew up in the rural town of Tetetla, Mexico, seeing firsthand how people can struggle to access antenatal and midwifery services.

“I was motivated to become a midwife out of love and dedication to pregnant women and children in the community where I am from,” she says. “Learning that trained midwives could decrease maternal deaths was my greatest motivation.”

[Pictured above] Erika wants to help women in her hometown of Tetetla in Mexico. © Tomas Pineda

-

Erika is completing her training at the Tulancingo General Hospital in Hildago. Once qualified, her dream is to work with other professionals to make more life-saving support available to rural communities, including her hometown. “Maybe if the hospital is too far away, they will have another place closer,” she says.

[Pictured above] Erika takes a moment to reflect on her midwife training. © Tomas Pineda

-

Worldwide, 900,000 more specialist midwives are needed.

To close this gap, UNFPA is working in some 125 countries to strengthen quality midwifery training and to hold decision-makers, donors and health institutions accountable for their commitments to strengthen midwifery care and to protect maternal and newborn health.

Midwife Leonor says it is essential that midwives and obstetric nurses are recognized as the specialists that they are – and that more women have access to them.

“We have a [general] model in Brazil where a doctor leads most of the childbirths in the hospitals. So we are building this autonomy as midwives, in this leadership role for maternal health.”

[Pictured above] Midwives provide many crucial services that can save lives. © Andrea Murcia

-

Without specialist care, the decisions women make ahead of labour are not always respected.

For instance, in Brazil, 70 per cent of women in early pregnancy say they want a vaginal delivery, but more than half of babies (57.2 per cent) are born by Cesarean section. These C-sections are not all inevitable.

For women who did deliver naturally, only 5 per cent went through the experience without unnecessary interventions, as the Birth in Brazil study found.

[Pictured above] Leonor offers choices to women in her care. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

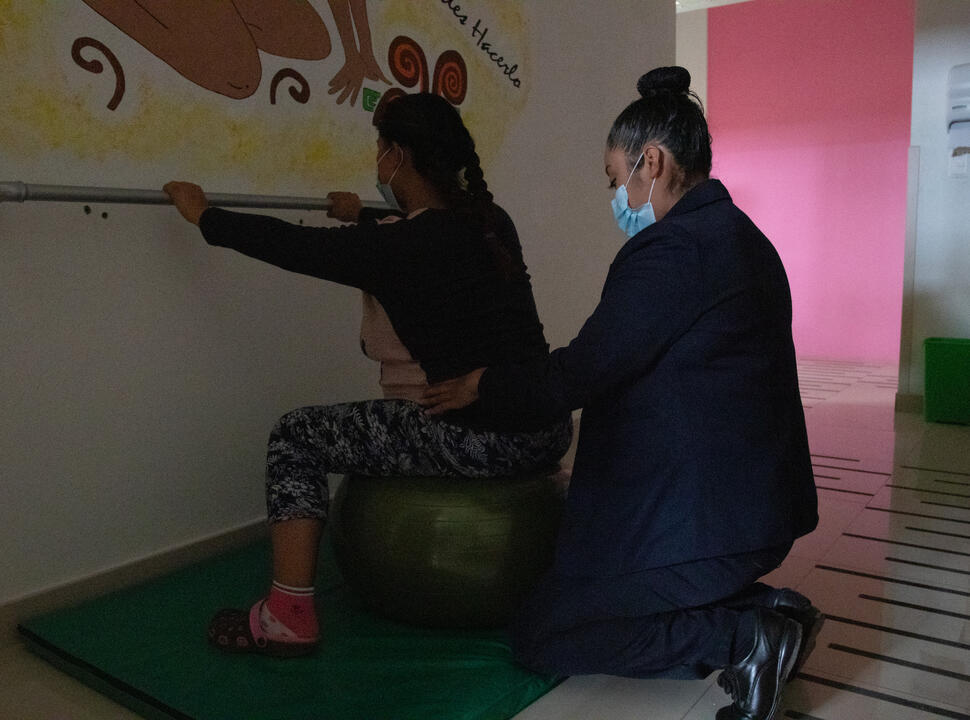

In Mexico, Erika is also keen to decrease the number of C-sections for women who prefer a vaginal birth.

“We can make some manoeuvres so the baby is in the right position, helping the women try different positions, doing exercises such as psychoprophylaxis,” a method for coping with labor pain by using patterned breathing techniques and relaxation. She also offers options including aromatherapy, massage, music and water birth.

[Pictured above] Erika helps women exercise and find comfortable positions. © Andrea Murcia

-

Leonor says it’s not her role to be directive, but to assist women to be in control of their own labour, while providing knowledge, practical skills and support.

“Creating a bond during prenatal care is very important,” she says, explaining that this allows each woman to get to know the professional who will be with her during labour.

“We are women taking care of other women.”

[Pictured above] At a prenatal class, Leonor shares information with women and their birthing partners about the choices available to them. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

It’s time for choices to be put into action.

Birthing plans are designed to be adaptable, with respect for women’s choices – from the lighting and temperature in the room, to the positions they want to try, to the way they want to manage pain.

[Pictured above] Leonor supports a woman through her labour. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

Leonor helped to safely deliver baby Téo. He is 11 hours old.

[Pictured above] Baby Téo snuggles in his crib. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

“It doesn’t look like you only gave birth [less than] 12 hours ago,” says Leonor, chatting with new mother Carolina.

Téo is Carolina’s third child. Like Erika, Carolina came to the Casa Angela birthing centre because she did not want another hospital birth.

This time, she says, “I felt my feminine strength much, much more. This was what I was looking for, to feel my freedom to do as I want; it felt exactly how it should feel. And that’s what makes the moment more special."

[Pictured above] Leonor provides postpartum support, including breastfeeding guidance. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

-

“When the baby is born, we put the baby close to the mother’s chest to feel her heartbeat,” says Elisa, the head nurse of the delivery room at San Andrés Hospital in Colombia.

She describes doing the same with fathers, to promote bonding between newborns and parents, and she makes it possible for fathers or birthing companions to cut the umbilical cord if they wish.

[Pictured above] Yolimar holds newborn baby Brenda while partner Giovani looks on at San Andrés Hospital in Colombia. Yolimar is Venezuelan, Giovani is indigenous, and they live on a rural reservation. © UNFPA/Carolina Navas

-

“To bring a person into this world, born healthy, without complications, to present him to his mother, it's an incredibly happy moment to welcome that little baby,” says Erika, the midwifery intern in Mexico.

[Pictured above] A newborn baby is delivered safely in Mexico. © Andrea Murcia

-

Nurse Elisa says UNFPA training has helped empower obstetric specialists to establish sexual and reproductive health as a right. The “extraordinary courses,” she says, “have changed me as a human being.”

Midwife Leonor shares Elisa’s sentiment. “It is important for us to keep fighting for human rights,” she says. “When we do training like this, see what women are still going through; we see how much we still have to fight for.”

In a world where a woman dies during pregnancy or childbirth every two minutes, midwives save lives.

[Pictured above] Leonor holds baby Téo in his softly lit room. © UNFPA/Tuane Fernandes

- Home

- Slideshows

- Taking the fear out of childbirth in Latin America

Taking the fear out of childbirth in Latin America

05 May 2023