News

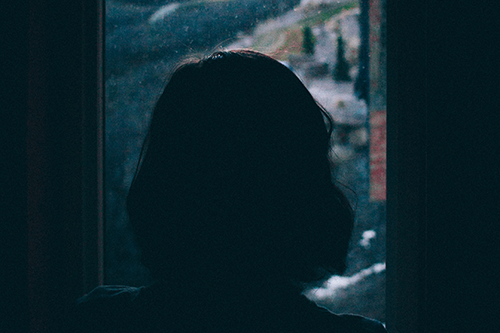

“Life became a cage”: Syrian girls shed light on conflict, vulnerability and cycle of abuse

- 26 November 2019

News

DAMASCUS, Syria – “Growing up, I felt as though my wings were slowly clipped against my will, and life became a cage from which there was no escape,” said Amal*, a Syrian adolescent from Qamishli. “An entire world waited outside where women were becoming leaders, scientists, engineers, but I was trapped in a different world where being a girl meant having no voice.”

Amal is not alone. Her words paint a grim picture of what it's like for countless girls growing up amid the Syrian crisis.

As the conflict nears its ninth year, the full scale of its death, destruction and displacement is hard to fathom. Violence pervades both the battlefield and the home.

Gender-based violence is rampant, data collected by UNFPA this year show. It occurs everywhere – homes, schools, marketplaces, streets – and has come to define how young girls perceive and interact with their communities.

“After the war came, we thought we would have to worry about fighter planes and bullets, but instead we found ourselves worrying about harassment, kidnapping and rape,” said Dalia*, from Idlib. “We don’t leave our houses anymore. Some girls cannot even go to school because their families won’t let them.”

UNFPA works with local partners to protect and empower women and girls affected by the crisis. Between January and September 2019, UNFPA reached more than 880,000 Syrians throughout the region, including refugees in neighbouring countries, with services to prevent and respond to gender-based violence.

UNFPA also collects information about the conflict’s impact on women and girls. Several recent analyses show that girls face significant challenges along the full continuum of their lives. For instance, girls report that fear of assault is leading families to curtail their freedoms and development.

“It began with the women in my family asking me where I go and who I talk to, telling me not to play with my friends outside,” recalled Nada*, 14. “Then I started sensing strangers watching me when I walked to school or sat outside with my friends. If a boy talks to me, I see people looking at me with aggression, as if I am somehow doing something wrong.”

Girls who do venture out often experience suspicion and invasive questioning. Girls told UNFPA that they had been accosted by strangers about matters such as their menstrual cycles and sexuality.

“Boys have all the freedom in the world, but we girls are expected to abide by too many rules. They treat us like criminals, not like people,” said Luma*, from Damascus.

“Many of the teenage girls we receive in our programmes struggle to interact with their male counterparts simply because of the fear and guilt ingrained into them by their families and communities,” explained one volunteer at a UNFPA-supported youth centre in Domiz 1 Camp in Iraq. “Breaking through this barrier is one of the most difficult challenges we face.”

While child marriage existed before the conflict began, assessments by UNFPA show that fear of violence and financial stress are pushing more families towards the practice. Many girls interviewed by UNFPA believed child marriage was an inevitability, no matter their desires or ambitions.

The practice is human rights violation known to unleash a cascade of additional harms. Child brides are more likely to drop out of school, diminishing their future prospects. They are more likely to endure adolescent pregnancies, risking their health and lives.

Child brides are also highly vulnerable to domestic violence, and less able to advocate for their needs. Countless case managers throughout the region have reported encountering Syrian girls in abusive marriages, becoming mothers while still children.

Experts are also seeing “serial marriages,” a form of exploitation in which a girl is briefly “married” to a client to justify transactional sex.

“These are perhaps the hardest cases to track and address, as such practices are done discreetly,” explained Ghaida, a volunteer at a women’s and girls’ centre in Iraq that treats survivors of sexual exploitation.

“It has become a recurring phenomenon for many girls in underprivileged communities,” she added. “They are either forced to enter into a series of short-term marriages, or worse, become unwilling participants in family-endorsed survival sex.”

Child marriages are often a secretive affair, but service providers witness the toll.

“When you do what I do, you see everything, and it becomes harder for families to lie. You know when a girl has been forced to marry, to share her bed and give birth against her will,” Umaira Salam, a midwife from Qardaha, told UNFPA.

“I’ve seen many girls enslaved like that, holding newborn babies when they’re as young as 13 years.”

*Names changed for protection and privacy