It’s not about the number, it’s about the quality of life

The world’s population reached 8 billion in November 2022. What does the general public think of this record number of people on the planet and how does this milestone affect them as individuals? How does it affect their communities and nations?

Interviews were conducted with several individuals from the Arab States, a region where a higher-than-average fertility rate (2.8 births per woman compared to the world’s average of 2.3) is occurring in the context of water scarcity concerns, accelerating desertification (Abumoghli and Goncalves, 2019), and frequent humanitarian crises. Have these trends affected people’s perceptions of population growth or influenced their decisions about having children?

One woman, Rama (name changed), said yes. “I don’t want to give birth to a child while living in these times,” the 30-year-old Syrian explains. “There are too many things to worry about today: safety, security, economic security.”

In her opinion, the population of Syria is too large for the level of services that are available. Conflict has weakened the social safety net. She adds that many people facing hardship today are having children without the means to care for them. “It’s everyone’s right to have a child, but maybe it’s best to wait for the right conditions.”Rama hopes to one day adopt one of the country’s many children who have been orphaned or abandoned.

Said (name changed), 45, says that the population of Oman may seem small compared to other countries in the region, but it’s growing fast, and it seems that people with fewer means are the ones having larger families. This is not a problem, he believes, so long as the country’s economy remains strong enough to provide jobs, especially for unskilled labourers. “I worry about what will happen if one day the economy takes a downturn and people lose their jobs,” he says. “And I worry about what a lot of unemployed young people will mean for stability.”

A key theme that emerged is that anxieties about population size are more often than not anxieties about being able to provide a good quality of life for everyone.

Khaled, 51, says that the problem in his country, Yemen, is that population growth is outpacing “development growth”. He says Yemen has a large and rapidly growing working-age population right now, and the country could, in his opinion, see faster economic growth if young people were educated, in good health and able to find good jobs. He says women in particular need to participate more in the country’s development. “So our population can be a positive thing,” he says.

Young people forge new paths

About one in six people in the world today are between the ages of 15 and 24, and the ranks of young people are growing rapidly, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Some policymakers view this trend with alarm, seeing nothing but potential for political upheaval and violence. Persistent negative stereotypes about youth frame them as a problem to be solved and a threat to be contained, according to The Missing Peace, an independent progress study on the United Nations Youth, Peace and Security agenda (Simpson, 2018).

But rather than being the problem, young people around the world today are increasingly part of the solution. Through their creative actions and “unapologetic advocacy”, young people are challenging the status quo in many sectors, according to the United Nations study. Youth creativity has reshaped culture and the arts. Youth movements have championed diversity and human rights. Energetic activism has offered an antidote to despair.

“The momentum surrounding the global youth agenda is larger than ever before,” says Idil Uner, who, at age 24, manages a flagship initiative of the Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth to recognize exceptional young leaders for the SDGs. Young people everywhere are making a difference, even though they rarely have a seat at the table where policy decisions are traditionally made, Uner explains.

While almost half of the world’s population is under age 30, the average age of political leaders is 62 (Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth, 2022). In some countries, the minimum age to run for public office is 40. Thus, most laws are enacted by people with a world view fundamentally different from those who have grown up in the fast-moving, crisis-beset, Internet-fuelled world of 8 billion.

“For generations before us, power was something exclusive. It was hierarchical, bureaucratic, formal and institutional,” Uner adds. But for most young people today, she says, “Power means transparency not secrecy. Power is fluid, not hierarchical. Power is in mobilization… In many ways, young people are already designing their own futures by reimagining the way our systems operate and by demanding true power-sharing within those systems.”

Gibson Kawago, for instance, a 24-year-old climate entrepreneur, radio personality and youth mentor in the United Republic of Tanzania, says, “Every young person should identify a problem in their own society and come up with a solution. That is the easy way for us to create solutions for the future.”

At age 14, he created a solar battery to help members of his unelectrified village. Later, with the help of a business incubator, he started his own company, WAGA TANZANIA. The company recycles lithium-ion batteries and produces durable and affordable battery-powered products. Since 2019, WAGA has recycled over 3,100 lithium-ion batteries and created 32 jobs, all while keeping hazardous materials out of the environment. On top of that, Kawago’s can-do spirit and empowering messages reach a radio audience of some 12 million.

Another youth leader, 24-year-old Paul Ndhlovu, from Zimbabwe, has an outsize influence. At Zvandiri (meaning “As I am” in the local language), an organization that provides peer-led support to HIV-positive young people, he has produced around 100 radio shows reaching an estimated 180,000 people over a recent 10-month period. Ndhlovu has seen policy changes informed by the show and by the group’s advocacy. “It’s all a collective effort,” he stresses.

These stories suggest the scope of what young people can accomplish when their talents are supported and when they are included in decision-making. “Ultimately we are the ones most impacted by the choices we make, or fail to make, today,” Uner points out.

With covert contraceptive use, women challenge men’s power over childbearing decisions

On her rounds in rural Ethiopia, health-care extension worker Amsalu goes door to door, delivering contraceptives to women who would otherwise not have access to them. The husbands of most of her clients know about the contraception — but a few do not.

“These women are already mothers with three or four kids,” says the 36 year old, who began doing this work 14 years ago. “They hide contraception because the husband wants more children but she has had enough or just wants to take a break.”

An estimated 7 per cent of married women who use contraception in Ethiopia are using it covertly (PMA Ethiopia, n.d.). Covert use is not unique to Ethiopia, however. It happens in many countries, with recent estimates from sub-Saharan Africa ranging from about 5 per cent in Kano, Nigeria, to more than 16 per cent in Burkina Faso (Sarnak and others, 2022).

Women typically resort to covert use in response to their husbands’ opposition. Some men think that a woman’s use of contraception means she is having an affair. Others object to contraception because they believe it can harm their wives’ health. Some say it goes against their religious beliefs. Still others want their wives to keep having children. In many countries, women tend to have less power in health-care decisions (Smith and others, 2022). That means when a man forbids his wife from using contraception, her only options may be to go without or to use covertly.

Amsalu says that women in her area prefer injectable contraceptives because they last for three months and are not visible. In the capital of Ethiopia, however, women who hide contraception from their husbands prefer implants and intrauterine devices, according to Gelila, a family planning services provider. “We can be asked to hide the scars from implants so their husbands don’t see them,” she says.

“Women hide contraception because they are afraid,” she adds. They are dependent on their husbands and fear what might happen to them if they are caught. The consequences can include everything from violence to divorce. “I remember one time, a man brought his wife into the clinic and demanded that I remove her implants then and there,” Gelila says.

Despite the risks involved, some women still choose covert use in response to “pregnancy coercion”, according to Shannon Wood, a Johns Hopkins University researcher who studies the social determinants of women’s health, gender-based violence, and adverse reproductive and sexual health outcomes. An estimated one in five Ethiopian women aged 15 to 49 have experienced pregnancy coercion, which can take the form of a husband forbidding family planning, taking her contraceptives away, threatening to leave her if she doesn’t become pregnant, or beating her for not agreeing to get pregnant (Dozier and others, 2022).

Even though covert use persists in the capital of Ethiopia and in rural areas, Gelila and Amsalu say they are seeing less of it today than they did a decade or two ago. “Nowadays, men are more open and understanding,” Amsalu says.

“Ideally, a couple would discuss using contraception,” Gelila says. “But if that doesn’t work, a woman may take action and use it even if her husband disagrees. It’s empowering for her to do what she has to do to time or space her pregnancies.”

Family planning: a climate change survival strategy

For some women, family planning can be a question of life and death. When there is no money to feed additional children, keeping families small is one way for women to cope. That is the case for Pela Judith, who lives in the Grand Sud, or Great South of Madagascar, a region now facing its most acute drought in 40 years (Kouame, 2022).

“I used to cultivate cassava and other grains,” she says. “The children went to school while we were in the fields.”

It’s a life the 25 year old barely remembers. “The droughts have changed many things. Now everything has become expensive — food, water. We had to stop schooling for two of the children.”

The drought has caused severe food shortages for more than a million people. For Pela Judith, it coincided with another tragedy: her husband fell ill and became partly paralysed. The family sold their land to pay for treatment and moved to the city to find work. Pela Judith is now the sole breadwinner, washing clothes or carrying water for money. For her, contraception is a necessity. “I am not even able to feed my four children, so giving birth to another child is not in my plans anymore.”

Pela Judith is not alone; many women are choosing to limit their family size in response to climate catastrophe (Staveteig and others, 2018). But not everyone makes the same choice. Some evidence shows that, while some women in Bangladesh and Mozambique preferred not to have children because they could not ensure their survival, others wanted to increase their family size by at least one son, which was seen as helping the family’s security (IPAS, n.d.).

For Volatanae, 43, reliance on a man was never an option. She works as a street hawker in the Madagascan city of Majunga, more than 1,500 kilometres away from her four children, who live with her parents. Abandoned by her children’s father, Volatanae alone shoulders the responsibility for making money to send home so her children can eat.

In Majunga, she got into a relationship with a man who turned out to be abusive. “He kept beating me. Because of this, I can’t hear with my left ear, I can’t hear very well with my right ear either, and I can’t see very well with my left eye.” The injuries have left her struggling to make ends meet. For her, contraception is essential — for her own future and for her children’s.

“With the droughts, how will I be able to feed another child? It’s already very difficult for me to feed my four children. Since the droughts, I am really afraid of getting pregnant again… Thank goodness family planning is still available where I am.”

Wooing Balkan repats

They’re called repatriates, or “repats” for short, people who move back to their home countries after having emigrated. Some parts of Central and Eastern Europe — under pressure from low birth rates and high outmigration (Armitage, 2019) — are working to convince emigrés to return home, hoping to see their populations grow and to develop demographic resilience.

The Balkan diaspora, for example, is huge. With an estimated 53 per cent of the people born in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 45 per cent of those born in Albania, and 12 per cent of people born in Serbia living outside their countries (Migration Data Portal, 2021), government incentives to woo them back are no surprise. The “I Choose Croatia” scheme offers up to €26,000 in subsidies to Croatians who come home and start a business (Hina, 2022). Serbia has a sophisticated combination of tax relief, start-up help and attractive technology parks, and Moldova’s PARE 1+1 programme matches private investments into new businesses started by returnees (ODA, 2013).

“I received help from three different programmes in Moldova,” says Irina Fusu, a dental surgeon who returned after five years in Russia. “It wasn’t just money. I’m a doctor, and I didn’t know management, so I was helped with business courses by the government.” Her Da Vinci dental clinic won the “best dental clinic” award in 2020.

National governments are not the only ones helping people return. In Serbia, Returning Point is a non-governmental organization whose mission is to create a better climate for repats.“When I decided to return to Serbia, I reached out to Returning Point,” says Ivana Zubac, a financial controller who spent 20 years in Western Europe. “I took a chance to see what things were like here, and my quality of life is now much better.” Zubac now helps mentor other newly returned Serbians.

Also returning to Serbia is Jelena Perić, a paediatric nurse who came back from Munich, where she had been working since 2011. She received support from yet another source: the German aid agency GIZ. “I wanted to help families learn about breastfeeding, which is not very popular in Serbia,” she says.

Many countries are looking for longer-term solutions, as well. When people have a decent standard of living, secure and promising jobs, good education for their children, decent health care, and an enabling environment, there are fewer reasons for them to seek these abroad.

Senad Santic says a stronger private sector also helps retain young talent. He runs ZenDev, an IT company in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and believes job opportunities like the ones ZenDev and similar companies provide will help keep young people from leaving.

“The idea,” says Santic, “is to have conditions at home that prevent people from wanting to leave in the first place.”

Expectations about women’s roles at work and at home drag marriage and fertility rates to new lows

“I’m willing to marry if I meet someone who has the same view about marriage as I do and respects me,” sayss Yeon Soo, a 35-year-old doctor in Gyeonggi‑do, in the Republic of Korea. “But I don’t feel the need to get married if there isn’t anyone like that.”

She is not alone. Fewer and fewer Koreans are marrying today. A survey of 30-year-olds by the Korea Population, Health and Welfare Association revealed that 30 per cent of women — and 18 per cent of men — said they would not get married in the future. Today, the marriage rate is about two thirds lower than it was in the 1980s (Ki Nam Park, personal communication). And those who are marrying are marrying later. In the 1980s, the average man and woman married at age 27 and 24, respectively. Today, the average ages are 33 and 31.

What accounts for this trend? As Yeon Soo indicated, one reason is concern among women that they will have to forfeit careers and become stay-at-home mothers shouldering the full burden of housework and childcare. “I think the most important thing in marriage is whether my potential partner can fully respect and support my career,” she says. “Here in Korea, after marriage, a woman’s status can change. She is no longer a woman, but someone’s wife, a mother, a daughter-in-law.”

Yeon Soo is not unlike thousands of Korean women who are rejecting long-standing views of marriage as an obligation, one that comes with responsibilities for raising a family, managing the home, and being an obedient daughter-in-law, and are increasingly seeing marriage as a choice, one that does not entail sacrificing university degrees or professional lives.

An unstable labour market, where a large share of young people, but especially women, have part-time or short-term jobs, is partly to blame for fewer and later marriages, explains Ki Nam Park, Secretary-General of the Korea Population, Health and Welfare Association. “About 72 per cent of women have at least a college degree,” she says. “I think the increase in the age of first marriage reflects a social trend in which young people are now investing more time in their academic background and job preparation and want to prioritize finding and holding onto a good job.”

And with fewer and later marriages come fewer children. Unlike in many other developed countries, having children in the Republic of Korea happens almost exclusively within marriage, Park explains. So with marriage rates at a record low, the country’s total fertility rate of 0.81 is the lowest in the world.

The decline in births alarms some policymakers because it means the share of the population that is older is growing rapidly, and covering the costs of medical care and services for them “will be a huge burden on the younger generation,” Park says. “If the total population decreases, production and consumption will decrease, the economy will contract, and eventually the vitality of society will decrease.”

The country’s falling marriage and fertility rates are intertwined with gender-unequal attitudes about jobs, child-rearing and housework. Gains in opportunities outside of marriage — in the labour market and in wider society — together with increasing costs associated with raising children today mean that the traditional “marriage package”, where the woman gives up her job, stays home and raises children while the man works long hours and devotes little time to housework and childcare, has lost its appeal for many young women, especially those with high levels of educational attainment, according to a recent OECD study on the Republic of Korea’s rapidly changing society (OECD, 2019). And because childbirth remains strongly associated with marriage, the study says, the barriers young people face even in finding a partner while establishing themselves in the labour market also contribute to declining fertility.

The Republic of Korea is not the only country where fewer and later marriages go hand in hand with fewer children. In Japan, too, marriage rates have reached historic lows, and 25 per cent of women in their 30s say they have no intention of getting married (Government of Japan, 2022). Meanwhile, the average number of births per woman is about 1.3.

Like their Korean counterparts, many young Japanese women are saying maybe — or maybe not — to marriage and to having children because they want to keep their careers and avoid being saddled with unpaid house and care work.

“I want to be married one day, but only under certain conditions,” says Hideko, a 22-year-old office worker in Tokyo. “I would want to continue my job, and my partner and I would have to share the burdens of house chores and child-rearing,” she adds.

For many women considering marriage, the opportunity costs are high, explains Sawako Shirahase, a social demographer and senior vice-rector of the Tokyo-based United Nations University. The usual choice women have to make is between only two options, she says. “It’s either A or B: keep your job or take care of your family.”

But there are also economic reasons factoring into decisions about marriage and starting families, Shirahase says. Young people prefer not to marry or start a family until they can afford it, and that goal is becoming harder and harder to reach, with many young people today finding themselves in precarious work situations. “Having kids and raising them are expensive in Japan,” Shirahase says. “The costs of sending children to good schools are often too high for single-income families.”

But if both parents are working so the children can go to good schools, she adds, “Who will take care of the children and do all the housework? It’s traditionally the woman who is expected to take on all these family responsibilities by herself.”

And for those couples who think they are ready to marry and have a family, it may be too late to have children. Nearly one in four couples in Japan has undergone testing or treatment for infertility, according to findings from the Japanese Fertility Survey (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2022). In addition, some women in their 40s may never even have the chance to start a family because men may not want to marry someone they think won’t be able to have children.

Policymakers in both Japan and the Republic of Korea have implemented tax credits and taken other measures, such as expanding access to affordable childcare, to make it easier for couples to have children, if they want them. But some of the obstacles to marriage and starting families may take generations to dismantle. In Japan, this will inevitably entail changing deeply embedded norms, as well as economic systems, to make them more gender equal and conducive to balancing families and careers, Shirahase says.

Natsuko, a 32-year-old midwife in Yokohama, says that one day she’d like to spend her life with a partner and have children but adds that marriage and childbirth would greatly affect her career plan. “This would never happen to a man,” she says.

Similarly, in the Republic of Korea, Dr. Park says that what’s needed is “a social atmosphere in which men actively participate in housework and childcare”. At the same time, gender discrimination in employment and wages are a big part of the problem, she adds.

Saori Kamano, a sociologist at Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, says that you can’t force people to get married and have children, so “you have to transform systems and institutions, as well as the norms”, starting with shifting attitudes about gender roles. “This will take a long time, but our recent National Fertility Survey shows there are signs of change.”

Family-friendly workplaces to support demographic resilience

When Diana Donțu, in Moldova, found out she was pregnant with triplets, she asked her boss for flexible working arrangements. He agreed — these had become more familiar during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it made good economic sense to retain skilled employees. Donțu worked from home after the births and later went back to the office three days a week as executive director of Panilino, a cake factory. “Without these policies, I would have had to find another company, or stay at home,” she says.

And as her children grew older, Donțu was able to send them to a new day-care centre on Panilino’s premises. “Now if something happens to one of my children while I am at work, I can simply go over and see them,” she says.

Her experience is an exception rather than the rule in this region, where women often have to choose between career and family. A recent survey in Moldova revealed 9 in 10 women with children under 3 stay home (UNFPA and Ministry of Labour and Social Protection of the Republic of Moldova, 2022). The scarcity of family-friendly policies has had knock-on effects: people often have fewer children than they want, pushing birth rates down. In addition, businesses — already grappling with a shrinking pool of workers due to outmigration — fail to benefit from the skills of women who are unable to re-enter the labour force after giving birth.

Through a programme funded by Austria that supports gender-responsive family policies in Moldova and the Balkans, UNFPA advised Panilino executives on how to develop family-friendly workplaces and provided a grant to help open the day-care centre. Evidence shows that such policies — both at the national level and those implemented by the private sector — are powerful tools to shift discriminatory gender norms and redistribute unpaid care work so that both men and women can realize their career aspirations without foregoing having children. While the principal aim is to allow more people to balance work and family life, it also helps ease the pressure on young people to seek job opportunities outside of the country.

Albania is another country in the region adopting family-friendly policies, which include generous parental leave benefits — for women and men alike (UNFPA Albania and IDRA Research and Consulting, 2021). But even though paternity leave is now available, few men choose to take advantage of it. In South-Eastern Europe, only 3 per cent of men say they have taken paternity leave (UNFPA and IDRA Research and Consulting, 2022).

Ardit Dakshi’s experience suggests at least one reason why. His job as a systems engineer in Tirana made it easier for him to work from home when his wife gave birth to twins. “In the beginning, my co-workers laughed at me,” he says. However, he adds, “When my colleagues saw all the benefits, they started using paternity leave too.”

The populations of many countries in Eastern and Central Europe are falling quickly (Kentish, 2020). Some governments are worried that without more births, and in the absence of immigration, their economies will falter, and there will not be enough young workers to contribute to social support systems on which their ageing populations depend.

Some countries have resorted to government incentives to encourage people to have more children. Incentives vary widely and include payments to families who have more children, tax breaks for larger families, housing and car subsidies, and also awards for mothers with more than five children, and experience with “baby bonuses” shows that cash incentives or tax credits by themselves, particularly when they are modest, have a negligible impact on fertility rates in the long run (Stone, 2020).

A more resilient approach helps couples reconcile work and family to have the number of children they want.

Data and studies support the value of having workplaces that are family friendly and parental leave that is generous and equitable; in these conditions, women have more job opportunities and men share household tasks (Armitage, 2019).

“Taking paternity leave and connecting with my daughters is the single most important thing I’ve ever done in my life,” says Dakshi.

As Donțu takes a Zoom call, her son Alexandru climbs onto her lap. “He was a bit sick today so I brought him to the office. I could not do this without these family-friendly policies.”

For Donțu and Dakshi, flexible and adaptable working conditions have made all the difference.

Needs of infertile couples can be overlooked in a world fixated on population growth

About five years into her marriage, Pat Kupchi began wondering whether something was wrong.

Why wasn’t she pregnant?

Up to that point, she hadn’t given it much thought because she was focused on pursuing a law degree in Ahmadu Bello University Zaria in Nigeria’s Kaduna State. But once she finished her studies, people around her began wondering, too. “She’s done with school, now what is she waiting for?” Kupchi says about the pressures.

In Nigeria, a woman has five children on average during her lifetime. “In Africa,” Kupchi says, “you marry and 12 months later if you’re still without a child, it’s a problem.”

Kupchi and her husband went to a doctor who determined that blocked fallopian tubes were preventing her from becoming pregnant.

In 1997, the year when Kupchi received this news, assisted reproductive technologies were just becoming available in Nigeria. She went to a clinic that offered hope — in vitro fertilization. Back then, the costs were prohibitive. “People were sceptical about the procedure,” Kupchi says. “It was new, and it was expensive. Should I part with this much money?”

But the couple decided the prospect of having a child was worth the expense and the risk that it might not work. And in the end, the procedure resulted in the transfer of four fertilized embryos, one of which led to the birth, in 1998, of her daughter, Hannatu, the first publicly recognized “test-tube baby” in Nigeria.

“A child is a trophy, a diamond of life,” says Ibrahim Wada, the obstetrician-gynaecologist who provided Kupchi’s treatment. “People give great value to having a child.”

Yet Dr. Wada acknowledges in vitro fertilization is often beyond the reach of many infertile couples. One cycle of in vitro fertilization in Nigeria costs between $2,000 and $3,000 (Fertility Hub Nigeria, n.d.), while per capita GDP is about $2,100 a year (World Bank, n.d.). To help, Dr. Wada set up a foundation that each year covers all or some of the costs of about 250 cycles of in vitro fertilization.

“I have encountered people who have had their backs to the wall in resource-poor settings,” he says. “You feel the weight of it when you see they are at a dead end.”

Some couples who cannot afford or access care resort to traditional, unproven and at times dangerous infertility treatments. Some involve plant-based remedies, Dr. Wada says, while others involve substances such as table salt and gin (Subair and Ade-Ademilua, 2022) or even “corrosives” that can cause permanent harm.

In Nigeria, when women cannot become pregnant, they are usually the ones blamed for the problem, even though male factors, such as low sperm counts, play a role in nearly three in five cases of infertility in the country (Umeora and others, 2008). Pregnancy and motherhood are “inextricably wrapped up in perceptions of femininity, and infertility can evoke a pervasive sense of failure as a woman” (Olarinoye and Ajiboye, 2019). “Women who can’t have children are stigmatized,” Dr. Wada says.

One study of Nigerian women with infertility found that 37 per cent of their male partners reported having taken another wife, and 12 per cent of husbands said they were planning to divorce their wives (Salie and others, 2021). For women, divorce can mean exclusion from family and community, as well as economic catastrophe for those who are not financially independent.

But attitudes may be changing, with some men acknowledging they are part of the problem — and need to be part of the solution. “Today, more men are accompanying women to fertility clinics. It’s no longer just ‘her fault’,” Dr. Wada says. “Back in 1994, you would hardly ever see men together with their wives at consultations.”

Still, Nigeria and many other countries have a long way to go to upend the view that a woman’s value depends on how many children she bears.

One way to make fertility care more accessible is to start approaching infertility in the same way as any other condition that requires treatment, Dr. Wada says, rather than as elective procedures available to those who can afford them.

In 1994, at the ICPD, 179 governments agreed that “all countries” should strive to give everyone access to reproductive health care, including “prevention and appropriate treatment of infertility”, through primary health-care systems. Yet few countries, if any, have reached that goal.

“Isn’t it ironic that people are worried these days about having too many children, when there are so many who would be happy with just one?” Kupchi says.

Imagining a better future

For half a century, scientists have been warning, with increasing urgency and ever-shortening timelines, of the impacts that climate change could exact on our future. After years of climate catastrophes, the reality of this threat has settled deeply in the psyches of younger generations, leaving many to question the most fundamental of human endeavours: whether to start a family.

A 2021 University of Bath study, the largest of its kind, found that 39 per cent of 10,000 people — aged 15 to 24 across 10 countries — felt hesitancy about having children “because of climate change” (Hickman and others, 2021). The percentages were higher in Brazil and the Philippines (48 per cent and 47 per cent, respectively) than in countries in the global North. The top-line results of a 2020 Morning Consult poll revealed 11 per cent of childless adults in the United States say climate change is a “major reason” they don’t currently have children (Jenkins, 2020).

Population alarmists might assume that planned childlessness is an effort to avoid contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. But a 2020 study found that “concern about the carbon footprint of procreation was dwarfed by respondents’ concern for the well-being of their existing, expected or hypothetical children in a climate-changed future” (Schneider-Mayerson and Ling, 2020). One 31-year-old woman in the study wrote, “ I dearly want to be a mother, but climate change is accelerating so quickly, and creating such horror already, that bringing a child into this mess is something I can’t do.”

Josephine Ferorelli first heard about climate change in the late 1980s, as an 8- or 9-year-old child in the United States. The experience felt surreal because of the resounding silence — like a taboo — about something so immense and consequential. Why weren’t people talking about it? When she met Meghan Kallman, a sociologist and activist who now serves as a Rhode Island state senator, about a decade ago, “We had a shared interest in climate activism,” she says, “and then it went into another direction.” Together, she and Kallman created Conceivable Future, described on its website as “A women-led network of Americans bringing awareness to the threat climate change poses to our reproductive lives, and demanding an end to US fossil fuel subsidies.”

“We suspected that other people needed to have this conversation, too,” says Ferorelli. That suspicion proved well founded: “Can we have three kids and truly be good to the Earth?” asks an anonymous 21-year-old on the site. “I keep hoping if I raise them well they will create a future better than the one we currently see looming in front of us.”

Many questions arise as well: How do you talk to kids about climate change? How do you channel despair? Is it selfish to have kids? Is it selfish not to? And if we don’t, where do we place the love in our hearts? The co-founders reject prescriptive answers, especially ones that generate guilt or point fingers at global population growth as the cause of climate change. An emphasis on individual sacrifice and responsibility is misplaced, they say, and does not reflect the actual large-scale, systemic causes of climate change, or the possible solutions to address it. “Our organization doesn’t take a position on what people should be doing with their reproductive lives at all. We just make space for people to talk about what they feel,” Kallman says.

“What we’re both most interested in is: how do you make sense of this in a way that takes us somewhere better instead of letting us stew in our juices about what a bad situation this is?” Kallman explains. For both women, the only right answer is decisive action on climate change. “The kids angle is a way to talk about, to connect with who has skin in the game and what that feels like,” Kallman continues, adding that they want to see action “around decarbonization and sustainability of the economy, not around policing women’s bodies. It’s just so weird to me that it’s so much easier to tell a bunch of women what to do than it is to tell a bunch of fossil fuel companies what to do”.

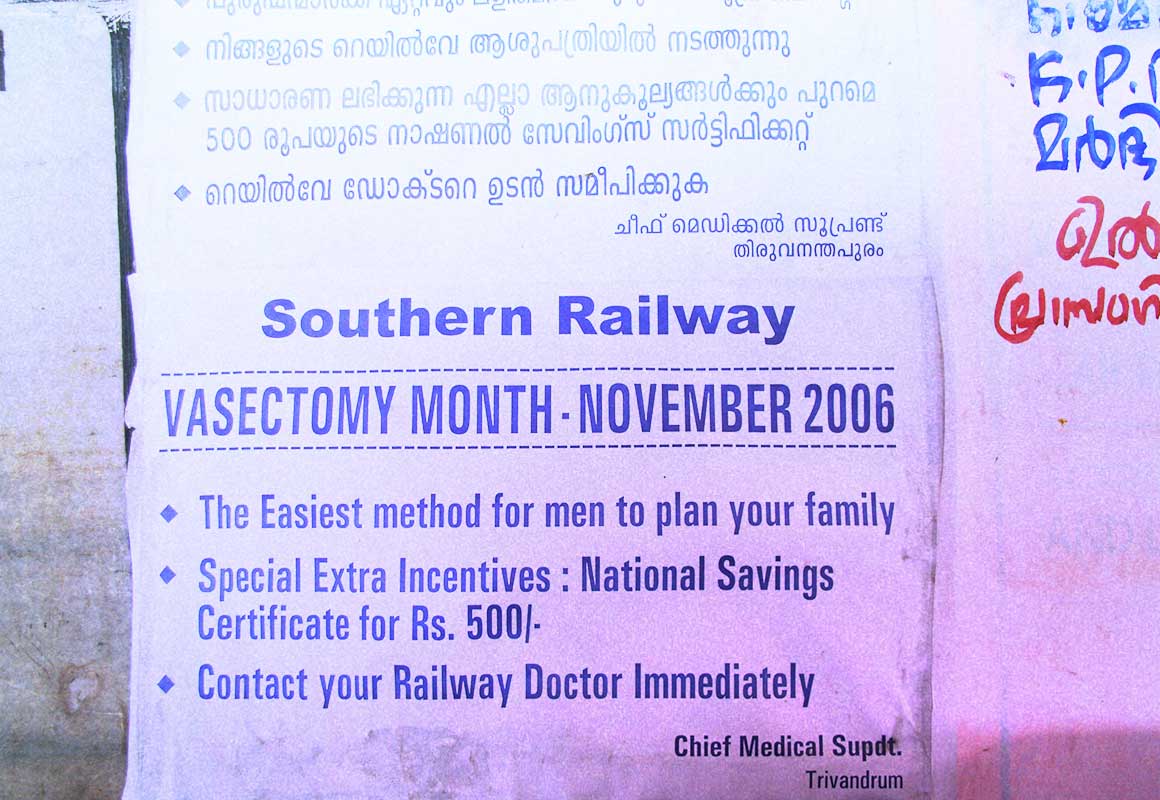

Viewing vasectomy as an empowering act of love

“I love my career,” says Joseph Mondo, a vasectomy provider in the rugged highlands of Papua New Guinea. His work takes him into the bush for weeks at a time, accompanied by four or five volunteers to carry the equipment needed to conduct non-scalpel vasectomies for men who have chosen not to have more children. They serve communities with little access to health care. An outreach officer for Marie Stopes Papua New Guinea, Mondo says he cannot keep up with the demand for his services. Most of his clients have already fathered six or seven children, he says. Often, he works late into the night to attend to men who shy away when others are around.

Everywhere, but especially in isolated rural areas where family planning services are not available, vasectomy — a quick and almost foolproof means of preventing pregnancy — makes sense and can save lives for those whose families are complete. It’s far safer and more affordable than female sterilization, which is globally more common — by an order of magnitude (UN DESA, 2019).

Beyond giving men their own method of contraception, vasectomy liberates partners from the burden, side effects, expense, inconvenience and uncertainties of the available female contraceptive methods. A higher uptake of vasectomy could radically reduce the high percentage of unintended pregnancies, which is about one in every two (UNFPA, 2021). In short, vasectomy seems like it should be an attractive option for couples who don’t want more (or any) children. But its global prevalence, which has never been much higher than 2.4 per cent, seems to have declined since 1994, according to United Nations figures (UN DESA, 2019).

Vasectomy is more common in a number of developed countries, with Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and the Republic of Korea all having a prevalence of more than 17 per cent — and in Bhutan, where vasectomy is eight times more common than tubal ligation.

Why aren’t vasectomies more common globally? The idea of tampering with such a sensitive part of a man’s anatomy plays a role. Moreover, misperceptions about vasectomy abound: in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, where vasectomy prevalence is statistically negligible, the procedure may be seen as a loss of manhood on the one hand, or linked to promiscuity on the other (Izugbara and Mutua, 2016). There’s another contributing factor too: since the advent of “the pill”, contraception has more or less been relegated to the female sphere. Dozens of contraceptive products have been brought to market, all targeted for women.

But there’s a more fundamental logic at work, in the view of Jonathan Stack, co-founder of World Vasectomy Day, an organization responsible for providing around 100,000 vasectomies since 2013. “It’s like everything in the world: where’s the money?” he says. “There’s been no investment in marketing vasectomies because there’s nothing to market. All of the new contraceptive options on the market for women are big money,” he adds. “Vasectomy doesn’t make money. It saves you money.” According to a 2020 Johns Hopkins University publication, each vasectomy in the United States saves the health system close to $10,000 over a two-year period (USAID and Breakthrough Action, n.d.). The same publication notes that among countries involved in the FP2020 (now called FP2030) global partnership to support family planning, only 20 per cent of couples have access to vasectomy.

Stack says he is engaging and empowering men, unleashing what he sees as an “innate human desire to care for and protect their families”. Each year in November, the World Vasectomy Day organization launches its annual push, via social media channels, free vasectomy clinics, provider training programmes and multiple forms of advocacy. In 2022, a tenth anniversary campaign included a full month-long roster of events in Mexico and elsewhere, with the slogan: Rising up together out of love for self, each other, and our future! Through an agreement with the Ministry of Health, 400 doctors were mobilized to perform 10,000 voluntary vasectomies across all 32 Mexican states.

November 2022 also marked the launch of a World Vasectomy Day Academy, an online programme to teach the basics of vasectomy and a directory with links to more than 500 vasectomy providers worldwide.

Stack is passionate about the power that can arise from the positive inclusion of men in family planning and reproductive health, especially at a time when a new kind of masculine consciousness is emerging.

“What I can tell you is there’s a change happening, and the family planning world would do well to recognize it,” he says. “We can do a better job of getting men to show up as positive contributors to society… If you ask a guy why he’s getting a vasectomy — and I’ve spoken to hundreds — he’s going to talk about the love of his children or his family or the love of the planet — some expression of love will come up. Which is why we emphasize celebrating responsible men and talk about vasectomy as an act of love.”

For accurate and credible data, participation and trust are key

Good policymaking depends on good population data. To prioritize investment, address inequities and promote overall well-being, governments need to know how many people there are, and where and how they live. That, in turn, requires the participation of individuals. In recent years, governments in Ghana, Moldova, Nepal and elsewhere have adopted innovative approaches to collecting and analysing data, including measures to raise awareness of, and build trust in, the process.

In 2021, Ghana set the stage for the country’s most comprehensive, detailed and accurate population and household census since independence. But confusion about the purpose of the census, and misinformation about who would or would not be counted, led some groups to voice concerns about participating, according to Samuel Annim of the Ghana Statistical Service. “We knew we needed a solid public awareness campaign to help everyone understand that the 2021 census would count everyone and that the data we would collect would be critical to advancing social and economic development and reducing inequalities,” Annim says.

That meant both outreach to the general public and also direct engagement with religious institutions, schools and universities, the media and members of parliament. Organizers created the slogan, “You count, get counted.” The Ghana Statistical Service even commissioned one-act plays performed by student drama clubs to raise awareness about the census and help communities understand what to expect when census-takers came to town. Ghana also employed often-overlooked communities and vulnerable groups, such as persons with disabilities, in census operations as trainers, advocates and data collectors. “We wanted to be sure everyone who had a stake in the census had a role to play in it,” Annim says.

In Moldova, the government, the National Youth Council and UNFPA mobilized youth to go door-to-door and encourage people to participate in the 2014 census. While the effort led to greater participation, many Moldovans nevertheless went uncounted. To have a more complete picture of the country’s population size, the government took the unusual step of comparing data on energy consumption with the data generated through the census. In addition, border-crossing data were used to estimate, for the first time, how many people were living in the country and how many were leaving and returning. These data contributed to a better estimate of the number of people with “usual residence” in Moldova, leading the World Bank to revise the country’s economic status upward and to subsequent revision of other statistical indicators, including the country’s SDG baseline and targets.

Nepal in 2021 set out to count its entire population — no small task in a country with 125 ethnic groups and castes speaking 123 languages across seven provinces, 753 localities and 6,743 smaller “wards”. Building trust entailed launching an information campaign using the slogan, “My census, my participation.” Organizers also emphasized the data would be used to inform actions to achieve the SDGs, including measuring the extent to which Nepalis enjoyed their rights and had access to services. They also made sure that marginalized and vulnerable groups, including persons with disabilities, were involved in census operations. Women accounted for about half of all census takers and data processors.

In the end, for a census to have real value, the data must tell the truth and people need to feel confident that the information will benefit them, explains Annim. “That means aggressively pursuing a non-political agenda and engaging all stakeholders, including civil society organizations, religious bodies and vulnerable groups in the process,” he adds. “We need to make it clear that census data are key to ensuring that no one is left behind.”