News

Struggling to End Female Genital Cutting in Uganda

- 23 September 2004

News

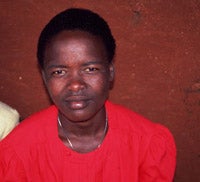

Betty Cheboi sits uneasily on a small wooden bench in her ramshackle shop perched on the edge of a jagged ravine in the remote hill community of Kapchorwa, near Mt. Elgon in western Uganda. A tiny woman, Betty is clearly uncomfortable as she adjusts her lifeless legs. She has endured bouts of pain and numbness in her lower body for the past 28 years, ever since was subjected to the practice of female genital cutting.

"I remember that awful day as if it were yesterday," she says in a barely audible voice. "I did not want to be circumcised, my husband did not want me circumcised, but the rest of the community did, and so I was tied up and held down while the 'cutter' did her business. It was the most horrific experience of my life."

" I was just 22 when they cut me. I had a life then and they took it from me. No girl or woman should have to endure this gruesome practice. "

--Betty Cheboi

"A few months later my husband abandoned me and I have been living alone in this shack for almost three decades," says Betty. "Only my mother helps me out."

Her two girls have families of their own and have moved away, and her two boys seldom come around.

Betty barely ekes out a living selling simple household supplies and a few drugs, such as aspirin. "I was just 22 when they cut me," she says, a deep sadness in her eyes. "I had a life then and they took it from me. No girl or woman should have to endure this gruesome practice."

Out of misfortune, Betty has found a new calling. She is now a vocal advocate for eliminating female genital cutting (FGC) in this remote, mountainous region. She is part of a growing network of women and men who are working for the complete elimination of this harmful practice through an initiative called REACH (Reproductive Education and Community Health) launched by UNFPA in the mid-1990s.

The initiative has reached out to communities in the region in a way never before attempted. Its approach is community-based and multi-sectoral. "We work on many levels here," explains Grace Mwanga, a nurse at the local youth-friendly health clinic in Kapchorwa. "We mobilize people at the community grassroots level, work with church leaders, village elders, local politicians, youth and most important of all, the women who perform the procedure and depend on it for their livelihoods."

Advocacy activities are aimed at a broad cross section of the population. "This integrated approach works well," points out Jackson Chekweko, coordinator of the project for the Family Planning Association of Uganda (FPAU), one of the implementing agencies. "It has allowed us to change attitudes and practices in a very conservative, traditional region in a relatively short period of time."

Attitudinal change is not easy, especially when confronting ancient practices and beliefs. "No one really knows when the practice of FGC began here," explains Chekweko. "It was started by the Sabine people many centuries ago. In the old days, women could be killed if they refused to go through with it. But we have made significant inroads in eliminating it."

Currently, the World Health Organization estimates that 130 million women worldwide have undergone some form of female genital cutting. This thousand-year-old tradition stubbornly persists across much of Africa and the Middle East. In sub-Saharan and North Africa, 28 countries routinely practice female genital cutting. WHO reports that every day some 6,000 young girls are subjected to the practice, often in unsanitary conditions with unsterilized instruments.

According to George William Cheborion, who, at 76, is Chairman of the Village Elder’s Association of Kapchorwa, REACH is rooting out the practice one village at a time. "Today less than 50 per cent of the entire population of this region practices FGC," he says with a satisfied grin. "And even in those communities that still allow the practice, it is getting rare. We were able to affect real and lasting change through our community outreach efforts."

The model developed by REACH is being replicated in other regions, even neighboring countries. "We are collaborating with groups in Tanzania and Kenya who are also working to eliminate FGC," points out Cheborion.

|

Chekweko agrees. "Community advocacy has really made the difference," he observes. "But the project got a big shot in the arm in 2002, when the African Youth Alliance (AYA) joined the fight to end FGC." AYA is funded by a generous grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and is administered by three agencies: UNFPA, PATH and Pathfinder International. Like REACH, AYA’s approach is youth-oriented and community-based. "It was a good marriage," says Chekweko, who is also the AYA focal point with the Family Planning Association of Uganda. "We needed more advocacy with young people and more health services designed for youth, and AYA provided that strategic support."

Beatrice Chelangat, REACH's Programme Manager in Kapchorwa, has been a community activist most of her life. "Our journey has not been easy, but we have noted a big change in attitudes regarding FGC," she explains. "Out of 10,000 Sabine girls only 1 per cent underwent genital cutting in 2003 and 2004."

In some communities change has been swift and dramatic. In the remote village of Cheptuya, buried at the end of a valley and reachable only by a washed out road, FGC dropped from 90 girls in the mid-1990s to 30 girls in 2000 to zero by 2002. "There the village elders stamped it out," says Chelangat.

Another reason why the practice is dying out fast in some areas is the fact that the project also focused on the cutters themselves. Sitting by a tent in a rain-soaked field is 80-year-old Kokop Night, a former cutter who, thanks to the project, has renounced the practice and vowed never to take up the knife again. Speaking through an interpreter she explains how she got involved. "My mother was a cutter, and her mother before her, as far back as anyone can remember," she explains in a harsh, scratchy voice. "It continued for so long because few saw the harm in it and, as cutters, we made a lot of money. I used to get 15,000 shillings per girl and might cut as many as 20 girls in one day."

Now that Kokop has ceased being a cutter, REACH is helping her find alternative sources of income. She may get a small loan to raise chickens. Though her standard of living has dropped, Kokop has no regrets about giving up the work. "This practice has to end," she says with finality. "It is too cruel."

In a small cluster of huts not far away from Kokop, several young girls explain why they will not allow anyone to cut them. "We have been sensitized on this issue," explains Shara Chekwech, a bright 17-year-old. "I talked to older women who went through with it and have suffered a lot since. I decided then and there not to allow anyone to do such a thing to me. And my parents agreed."

Shara’s decision was reinforced by school-based sessions, which emphasized life-planning skills. Most schools in the region have introduced life skills planning as part of the informal curriculum. Meanwhile, advocacy efforts by village elders, religious leaders and parents have reinforced the rejection of the practice among young women.

As a testimony to the success of the initiative, REACH received UNFPA’s annual Population Award in 1998. "It certainly hasn’t been an easy road," says Chekweko, "but we will persevere. We have momentum now and the will to change is visible."

Betty Cheboi has found some comfort in the fact that in her village and neighboring areas the practice has been stopped. "I speak out against FGC every chance I get," she says almost breathless. "And many young women listen to me. When I see that my words have reached them it is the only time I feel like smiling."

--Don Hinrichsen