News

Men of Honour: Male Leaders in Nigeria Work to Protect Women's Health

- 10 July 2007

News

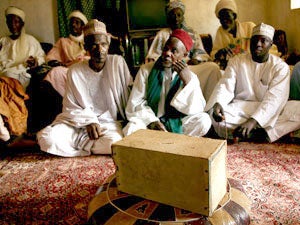

AMBURSA, Kebbi State, Nigeria—In the halls of an emir’s palace in northern Nigeria, a council of senior traditional leaders moves into the main receiving room, their flowing white robes coming gently to rest as they take their seats. A single official rises to deliver the message of Sarkin Kudun, the Emir of Ambursa.

“Childbirth is a universally celebrated event, an occasion for dancing, fireworks, and sometimes shedding tears of joy. Yet for many thousands of women each year, childbirth is experienced not as the joyful event it should be, but as a private hell that may end in death—and this is what we want to avoid in our community.”

An unusual speech to hear from an emir, perhaps, but one that is desperately needed. A woman giving birth in Nigeria is nearly 100 times more likely to die in childbirth than women giving birth in high-income countries. Poor quality obstetric care and limited access to or use of the care that is available, also greatly increases the risk that pregnant women will develop obstetric fistula—a debilitating condition brought about by prolonged obstructed labour. As many as 800,000 Nigerian women live with this condition, and 20,000 more join their ranks each year.

"You see, in our local communities, even if a woman is in a terrible way, she still needs her husband’s permission to leave the home and seek medical treatment. "

--Yusuf Lawal

The Nigerian Ministry of Health and UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund, are working together to improve this situation. Through various partnerships, they are upgrading the quality of reproductive health facilities, training medical staff, providing prenatal care to pregnant women, and distributing contraceptives and family planning information. But here in northern Nigeria, a heavily male-dominated society, these practical efforts are only part of what is needed. Here, to bring health care to women, one has to go through men first.

“You see, in our local communities, even if a woman is in a terrible way, she still needs her husband’s permission to leave the home and seek medical treatment,” says Yusuf Lawal, UNFPA Adviser in Kebbi State. “Men need to be convinced to let their women go.”

Working with the network of imams for the protection of women

Fortunately, the same traditional value system that presents this additional obstacle to women’s health also provides a way of overcoming it. UNFPA has joined forces with male traditional leaders, asking for their help in persuading Nigerian men of the importance of modern medical care for their pregnant wives.

One of UNFPA’s partners in this effort is the influential Kebbi State Council of Ulama and Du’at – the state’s network of imams, or Islamic religious leaders. In a region that is mainly Muslim, the religious authority of the imams can be an essential tool in persuading men of the importance of reproductive health.

“There are three contributing factors [behind men’s reluctance to let their wives seek medical care],” explains Sheikh Ummaru Ika, the organization’s leader. “The first is ignorance of why it is important. The second is fear that if a woman goes to the hospital, she could lose her womb. The third is poverty: men are afraid that sending women to the hospital will be costly.”

In response to these three problems, the imams have adopted a two-pronged approach. The first is persuasion: in their sermons at the mosques on Fridays, they preach the benefits of medical care for pregnant women and dispel myths surrounding it. They also encourage their followers to fulfil their Islamic duty to protect their wives by making sure they are properly cared for.

Overcoming the cost issues

Yet with all the explanation and convincing in the world, there still remains the problem of cost -- and it can be significant. In those hospitals that receive support from UNFPA, reproductive health services are provided entirely free of charge, but women still face the cost of transport to the hospital itself. And in other hospitals, care can be expensive. A pregnant woman with complications may have to pay as much as 10,000-15,0000 naira (approximately $80-$100) for care. In Nigeria, that figure represents a tenth of the average citizen’s annual income.

The imams are working to resolve this as well. In every village or small town in which they work, one person with a vehicle has been designated to provide transport to the hospital for any woman in labour or dire need. Each community also has a donation box, supervised by the imam himself, in which residents can donate funds for women to withdraw when they are in need.

The progress comes in small steps – but it is visible. “Now, women are generally taken to the hospital,” says Imam Mohammed Bellow, a look of pride on his face. “Even this very day, three women went there to give birth.”

Enlisting the support of powerful traditional rulers

UNFPA has also sought to work with the local emirs, the powerful traditional rulers in many areas of the north. In a country of over 130 million people – a vast amalgam of ethnicities, religions, and cultures – local traditional authorities still retain a great deal of influence.

“When the emir says to do something,” explains Kori Habib, UNFPA Program Officer in Nigeria, “people will do it.”

The emir of Ambursa is no exception, and he has put his authority to excellent use. Approached by the Ministry of Health and UNFPA for help in convincing his subjects of the importance of proper medical care for pregnant women, he responded with vigor.

“My community…recognized the fact that we owe it as a duty to give deserved attention to maternal health,” he says.

The emir has instructed his village heads, traditional leaders a level beneath him, to regularly speak with their communities about the importance of modern medical care for women. Pregnant women in his region can now turn to an organization called the Ward Development Committee, which, similar to the community boxes kept by the imams, provides funds for transport to the hospital or essential medication. Finally, his community actually helped pay for the construction of its own health care clinic—now used by more than 40,000 people—to which UNFPA donated reproductive health equipment, contraceptives, and training sessions for staff.

It is an unavoidable fact that for the moment, men do hold the key to women’s health prospects in northern Nigeria. But with leaders like the ulama of Kebbi and the emir of Ambursa in charge, those prospects are improving.

-Arthur Plews