Shelter

From The

Storm

A transformative agenda

for women and girls in a

crisis-prone world

state of world population 2015

state of world population 2015We live in a world where humanitarian crises extract mounting costs from economies, communities and individuals. Wars and natural disasters make the headlines, at least initially. Less visible but also costly are the crises of fragility, vulnerability and growing inequality, confining millions of people to the most tenuous hopes for peace and development.

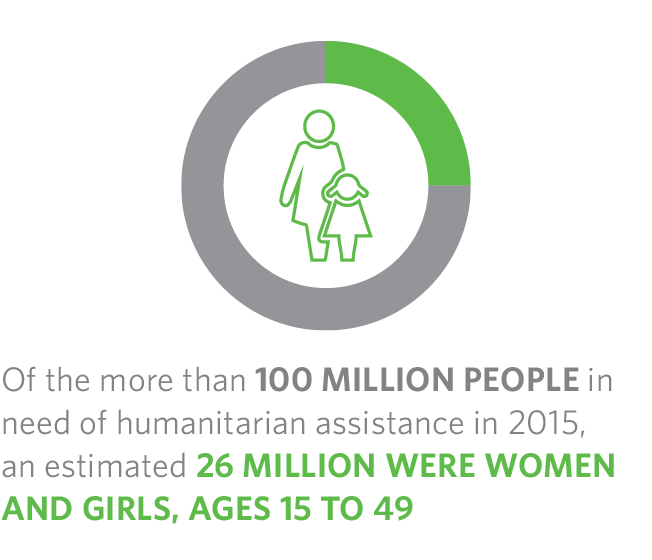

More than 100 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance. An estimated 26 million of them are women and adolescent girls of reproductive age

Risks

Women and girls are

disproportionately

disadvantaged

Natural Disasters

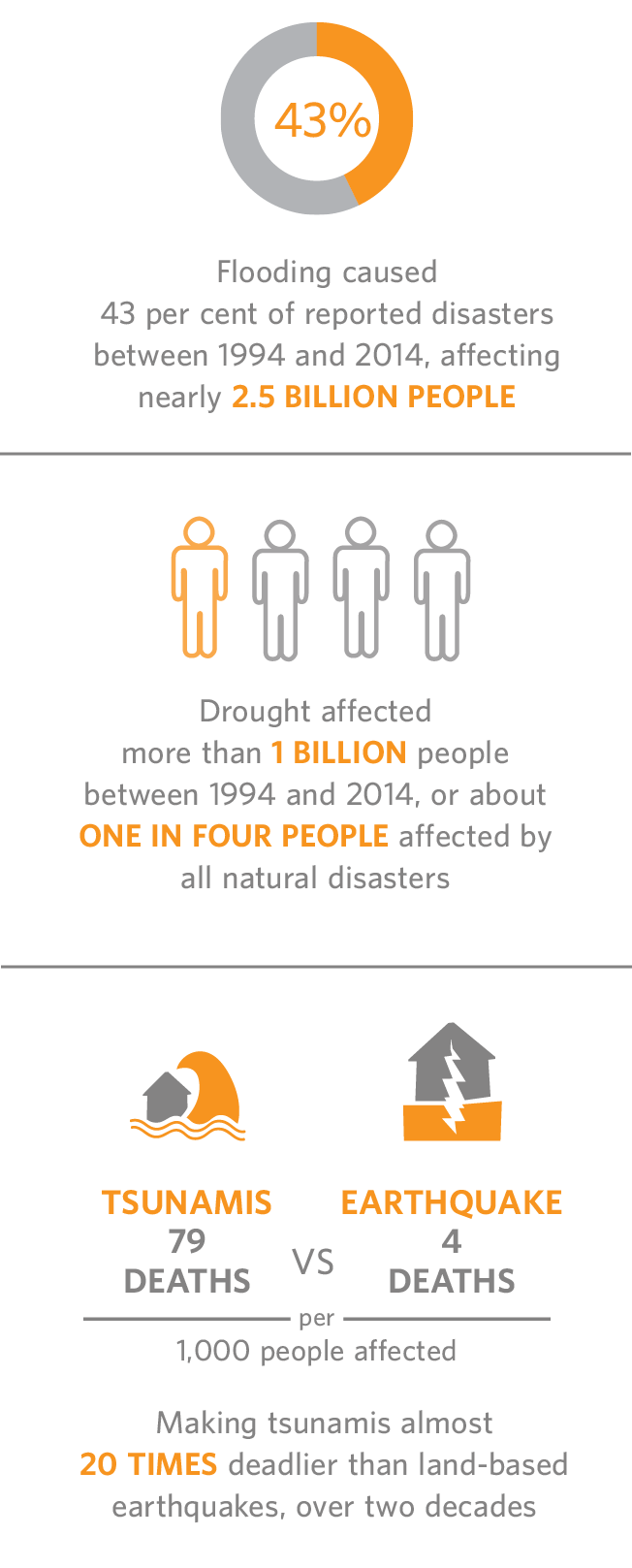

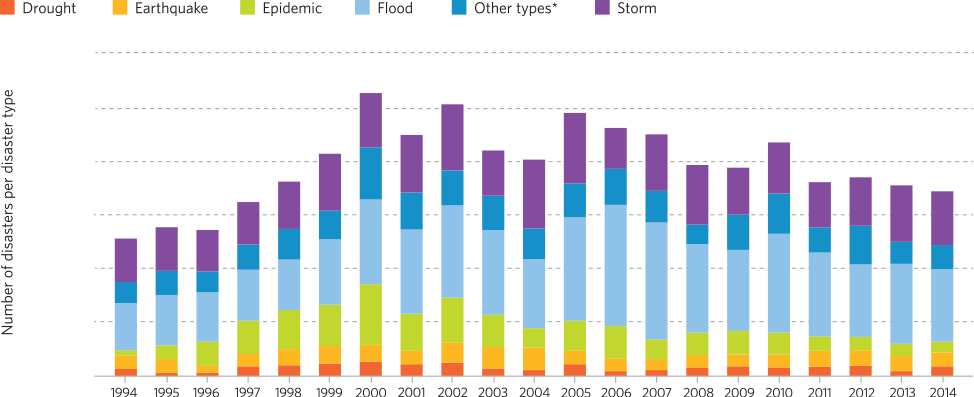

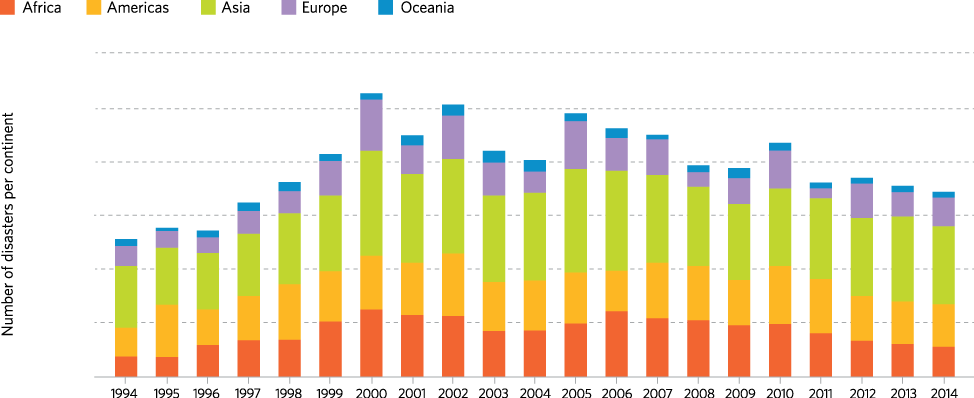

The number of natural disasters tripled between 1980 and 2000, followed by a slight decline, but still double the number today than what was recorded 25 years ago.

On average, more than three times as many people died per disaster in low-income countries (332 deaths) than in high-income nations (105 deaths). A similar pattern is evident when low- and lower-middle-income countries are grouped together and compared to high- and upper-middle-income countries. Taken together, higher-income countries experienced 56 per cent of disasters but lost 32 per cent of lives, while lower-income countries experienced 44 per cent of disasters but suffered 68 per cent of deaths.

For each person who dies in a disaster, there are hundreds more who are affected by it and require immediate basic survival needs, such as food, water, shelter, sanitation or immediate medical assistance. Those affected by a disaster often lose their homes and livelihoods, become separated from families, face a lifetime of illness, disability or restricted opportunities, and are displaced from their communities.

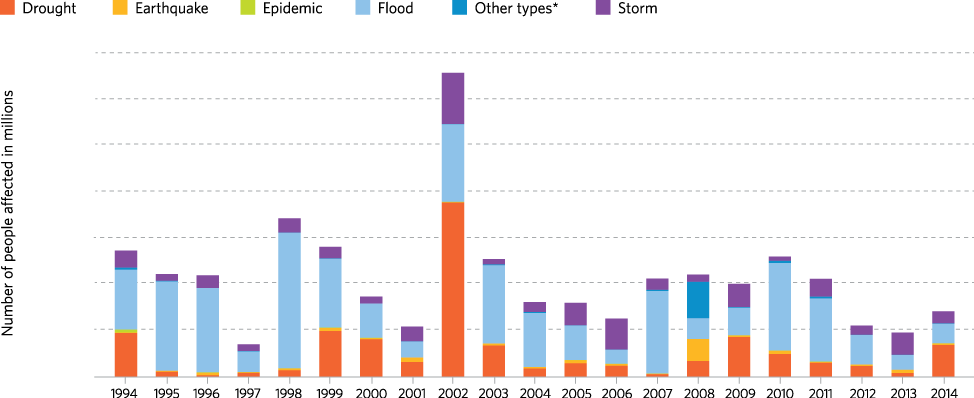

While disasters have been recorded more frequently during the past 20 years, the average number of people affected has actually fallen from one in 23 between 1994 and 2003, to about one in 39 between 2004 and 2014.

Controlling for population growth, the likelihood of being displaced by a disaster today is 60 per cent higher than it was four decades ago. Over the last 20 years, there have been an average of 340 disasters per year, affecting 200 million people annually, taking an average of 67,500 lives a year.

Rajina Tamang with her baby amid the rubble of what remains of Kuni village, which was destroyed when a 7.8 earthquake struck central Nepal.

Photo © Panos Pictures/Brian Sokol

Recorded Natural Disasters, Worldwide, By Type - 1994 to 2014

Estimated Number of People Affected By Natural Disasters, By Type - 1994 to 2014

Recorded Natural Disasters, By Region - 1994 to 2014

Estimated Number of People Affected By Natural Disasters, By Region - 1994 to 2014

Conflict

The Second World War, the largest conflict in the modern world, remains humanity’s reference point for mass harm. About 3 per cent of the world’s people died as a direct result of that conflict or its prelude and aftermath. Meanwhile, more than one third of the world’s people were affected by it. For each death, therefore, 10 other lives were radically disrupted.

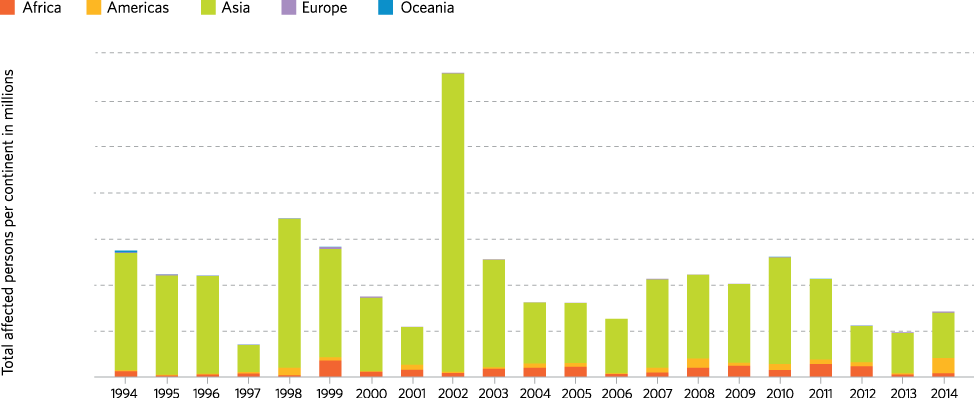

In 2014, the total number of refugees and internally displaced people worldwide reached 59.5 million, the highest number since the Second World War. The number of internally displaced people doubled from 2010 to 2015.

More than half of all new refugees in 2014 came from Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia and Sudan. More than half of all internally displaced people reside in Syria, Colombia, Iraq and Sudan.

Today, about one in four people in Lebanon and one in 10 in Jordan is a refugee. Today, only about one in three refugees resides in a camp. Two in three today live in urban areas.

About two-thirds of the world’s refugees are in situations of seemingly unending exile, with the average time spent that way reaching 20 years. The 25 countries most affected by a prolonged refugee presence are all in the developing world.

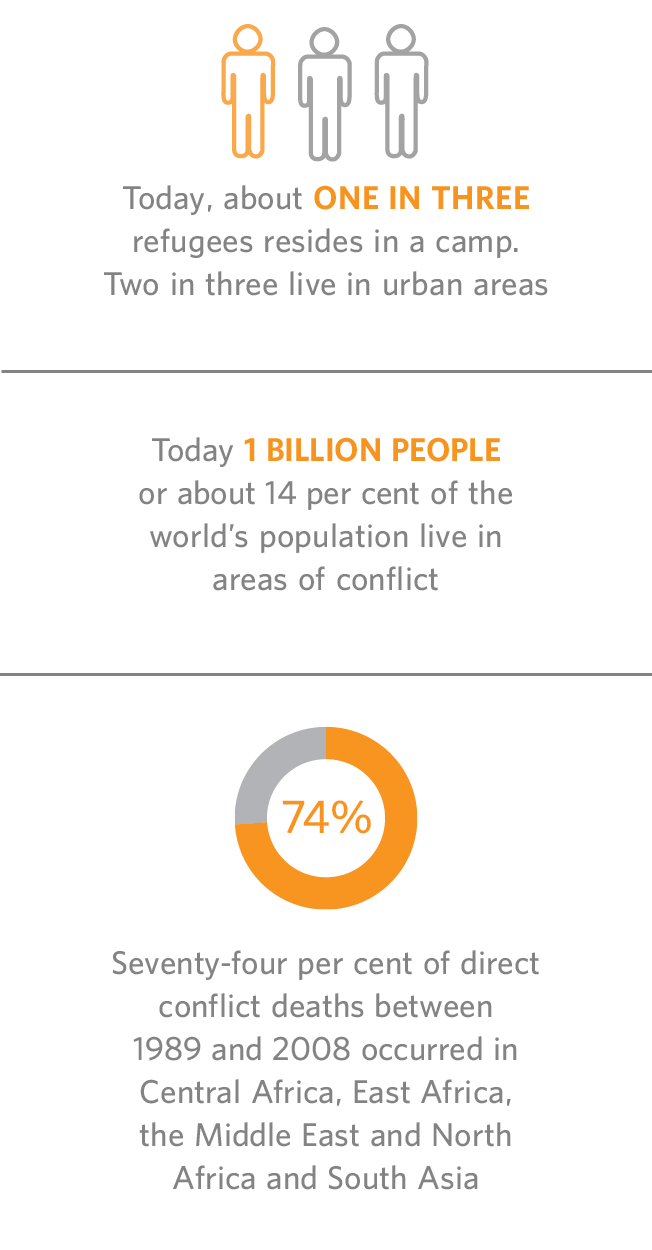

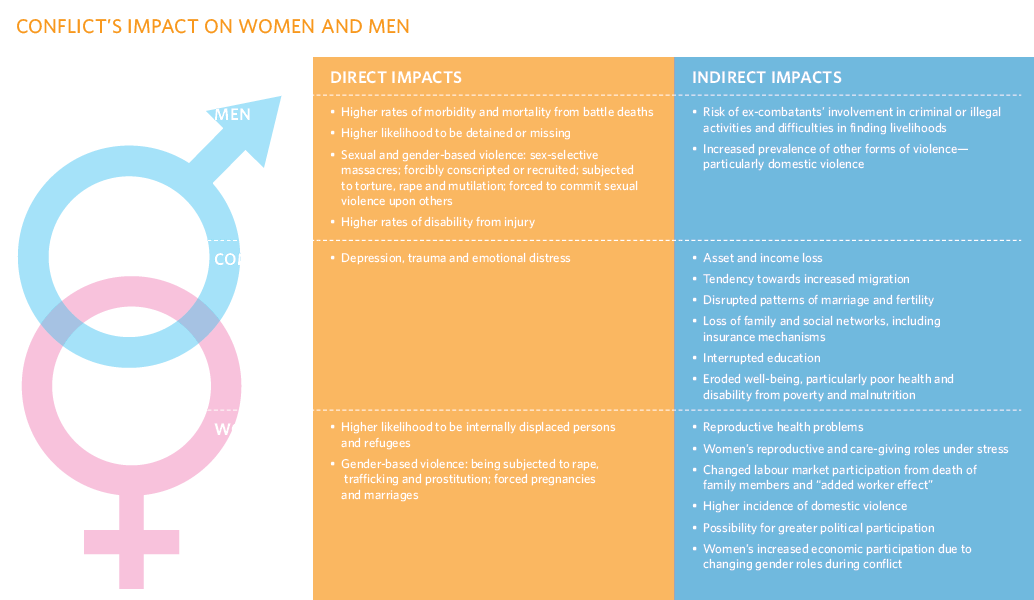

Men are much more likely to die directly and during conflicts, whereas women die or are otherwise harmed more often of indirect causes after a conflict. Every estimate of direct conflict deaths suggests that more than 90 per cent of all casualties occur among young adult males.

Fragility and Vulnerability

Fragile States are home to one third of the world’s poor. More than 1 billion people, or about 15 per cent of the world’s population, are in extreme poverty, according to estimates from the World Bank. Extreme poverty, previously concentrated in East Asia, has shifted to sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, which today accounts for 80 per cent of the world’s poor, the majority of whom are women and children.

The poor are especially vulnerable to the effects of conflict, and various measurements of fragility suggest that high levels of poverty and income inequality can contribute to instability. The poor have fewer economic, social and other resources to help them withstand or recover from conflicts, which can in turn exacerbate poverty.

There are many explanations of fragility and its causes. But regardless of the definition, fragility is closely linked to forces such as poverty, inequality and exclusion, which disproportionately affect women and girls.

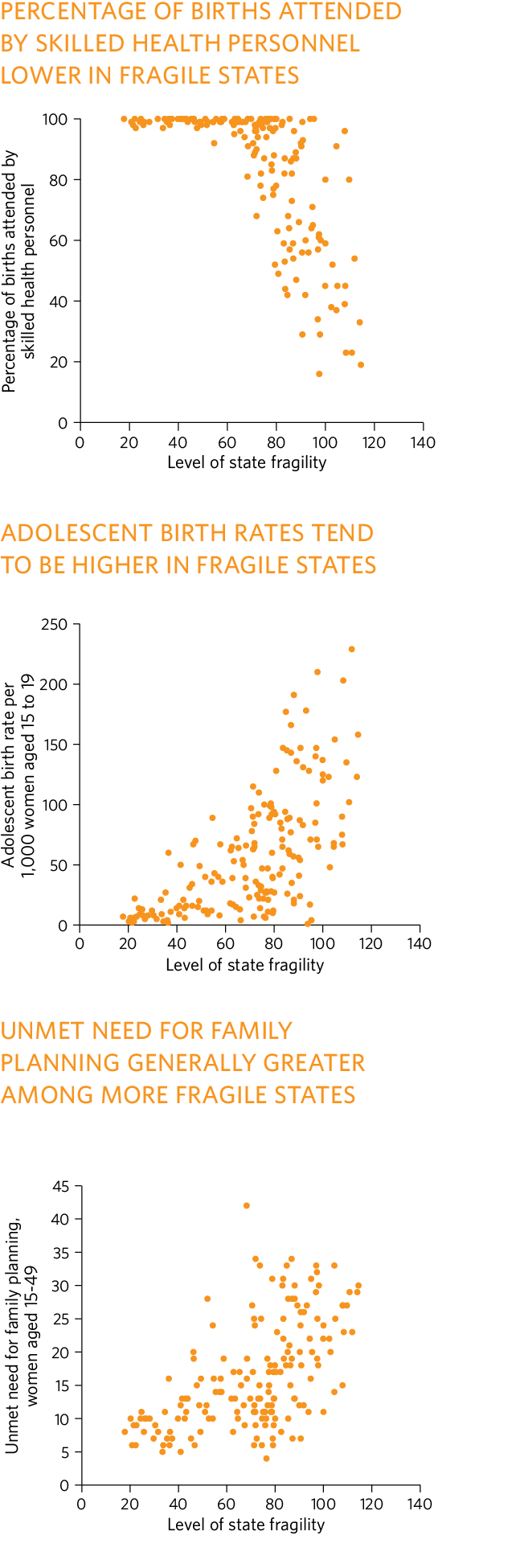

When States’ fragility is matched against key reproductive health indicators, correlations emerge, showing that extremely fragile countries are likely to have fewer births assisted by skilled attendants, higher rates of adolescent pregnancy and more unmet need for family planning.

Close to half the people in low-income countries in 2010 were in States that are fragile, in conflict, or recovering from conflict. These same areas accounted for 60 per cent of the world’s people who are undernourished, 77 per cent of the children not attending primary school, 70 per cent of infant deaths and 64 per cent of unattended births.

Conflict, violence, instability, extreme poverty and vulnerability to disasters are deeply interrelated conditions, which today prevent more than 1 billion people from enjoying the massive social and economic gains since the end of the Second World War.

A complex mix of overlapping hazards contributes to displacement and determines patterns of movement and needs in fragile and conflict-affected countries. Other additional aspects of vulnerability—gender, ethnicity, income and residence—appear to be associated with heightened chances for long-term harm and complicate recovery. And overlaying all aspects of social exclusion, poverty and low educational achievement create profound vulnerability.

Sapana Suwal, 25, with her children in shelter for earthquake survivors, Bhaktapur, Nepal. Photos © Panos Pictures/Brian Sokol

The Fund For Peace's Fragile States Index 2015

Risks to Women and Adolescents

Humanitarian crises disproportionately impact women and adolescent girls.

Whether sudden or protracted, crises expose women and girls—and their sexual and reproductive health and rights—to layers of disproportionate risk.

Conflicts and disasters can make a bad situation worse. For women and adolescent girls, the advent of a crisis can lead to an even greater risk of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, unintended and unwanted pregnancy, maternal morbidity and maternal mortality, as well as other risks to the health of mothers and newborns. Women and adolescent girls are also at greater risk of sexual and gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence, rape, early marriage and trafficking.

Women and young people do not all have the same story to tell. Their experiences are influenced by a complex intersection of factors, such as age, sex, marital status, economic status or place of residence. Other vulnerabilities depend on whether they are members of an ethnic minority, living with HIV or disability, refugees or internally displaced persons or poor, or have the support of family or have dependents.

The intersection of these factors, often in complex and multiple combinations, influence the risks and vulnerabilities faced by individuals.

40 miles from the Libyan coast.

Photo © Franco Pagetti/VII

Women do not stop getting pregnant or having babies when a crisis hits

Sierra Leone

An estimated 123,000 women were pregnant in Ebola-affected Sierra Leone in 2015.

Nepal

UNFPA estimated that there were approximately 126,000 pregnant women at the time of the April earthquake, including 21,000 of whom would need obstetric care in the coming months.

Philippines

An estimated 250,000 women were pregnant when Typhoon Haiyan hit in November 2013 and approximately 70,000 were due in the first quarter of 2014.

Vanuatu

At the time of Tropical Cyclone Pam (2015), there were an estimated 8,500 pregnant and lactating women in the affected provinces.

Although there are important differences among women and young people in any given crisis, there are two common overarching factors that contribute to heightened risk: The first is gender inequality, which not only continues during humanitarian crises but often increases.

Inequality manifests itself in less access to education, economic and political resources and social networks. It can also be fatal—when parents facing food shortages direct most or all nutrition to boys.

The second overarching factor leading to heightened risk is the breakdown or disruption of critical sexual and reproductive health infrastructure and services that occur in crisis settings, and the difficulties in accessing these services, where they still exist, as a result of chaos or insecurity.

Response

Essential actions and services

from the onset of a crisis

Until only 20 years ago, sexual and reproductive health took a back seat to priorities such as water, food and shelter in humanitarian response. But a wealth of research and evidence since the early 1990s has helped make the health of women and girls far more visible. Many humanitarian interventions now meet needs associated with pregnancy and childbirth, and seek to prevent and address vulnerabilities to sexual or gender-based violence and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

Not only is it more widely accepted that meeting these needs is a humanitarian imperative and a matter of upholding and respecting human rights, but it is also clear that ensuring access to sexual and reproductive health is a pathway to recovery, risk reduction and resilience. The benefits extend to women and girls—and beyond. When they can obtain sexual and reproductive health care, along with a variety of humanitarian programmes that deliberately tackle inequalities, positive effects ripple throughout all aspects of humanitarian action.

Family planning

In humanitarian crises where funding for life-saving interventions is limited, family planning is a sound investment. In general, each $1 spent on contraceptive services saves between $1.70 and $4 in maternal and newborn health care costs.

Last year, UNFPA provided contraceptives and other family planning supplies in emergency reproductive health kits, which targeted the delivery of services to 20,780,000 women, men and adolescents of reproductive age in humanitarian settings worldwide.

Family planning is an indispensable element of response, as well as rebuilding and recovery, and directly benefits women and girls through increased family savings and productivity, as well as better prospects for education and employment. It also improves health outcomes as fewer unintended pregnancies result in fewer complications during childbirth and fewer maternal deaths.

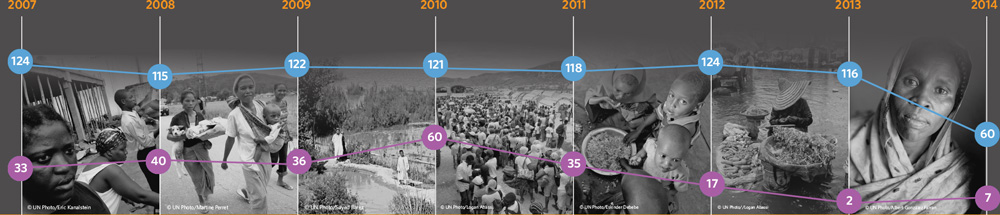

United Nations humanitarian response, 2007-2014

Healthy mothers

UNFPA’s role in any humanitarian situation is to ensure that women have access to safe delivery services, no matter what the circumstances, in order to protect the lives and health of both mothers and babies.

The 10 countries with the highest maternal mortality ratios in the world are affected by, or emerging from, war (World Health Organization et al., 2014).

Creative means have sometimes been used to ensure access to maternal and newborn health services to women who are distant or dispersed.

Community health workers responding to Ebola in Guinea, for example, used smartphones to register people exposed to the virus and relay critical information to health officials.

In Somalia, nurses used global positioning systems to facilitate the delivery of health services to internally displaced persons in remote areas (Shaikh, 2008).

Also in Somalia, UNFPA is supporting 34 maternity waiting homes for pregnant women with complications to provide care and protection until it is time for delivery at a health facility.

UNFPA Supports Access to Services By Women And Girls

Services and supplies provided January to September 2015 in Lake Chad Basin countries affected by Boko Haram crisis

Cameroon

4,075 kits for safe delivery distributed to health posts in camp and centres

5,400 dignity kits delivered to pregnant and vulnerable women and girls

10,000 male condoms distributed

110 women accessed contraception

11 case of rape clinically managed

30 district health staff and 40 community health agents trained and deployed

22 newly trained midwives deployed

5 youth centres equipped for skills development and adolescent counselling

4 public health facilities serving refugees equipped to provide quality reproductive health services

4 youth-and women-friendly spaces created in Minawao camp

Niger

53,312 condoms distributed

10,913 women and adolescent girls accessed family planning

1,458 women assisted for safe deliveries

1,407 dignity kits were distributed to refugees

906 women received antenatal care

118 adolescents and youth received training as reproductive health educators for refugees

40 health providers were trained

22 women survivors of gender-based violence received psychological support

Chad

28,000 condoms distributed

2,500 women, men, young people attended awareness-raising about gender-based violence

1,500 women received antenatal care

1,500 women received gender-based violence services

510 women assisted for safe deliveries

500 women accessed contraception

Nigeria

2,108,441 people’s awareness raised about preventing and responding to gender-based violence

27,293 women assisted for safe deliveries

22,000 women and adolescent girls received dignity kits

214 reproductive health kits (1,759 cartons) distributed, containing a range of life-saving medical equipment, drugs and other supplies

213 health workers and programme managers were trained in providing reproductive health services in humanitarian settings

56 midwives and nurses were trained in administering long-acting reversible contraception

Preventing and treating HIV

HIV has received progressively greater attention in humanitarian settings during the last two decades and receives greater funding and targeted assistance than other sexual and reproductive health topics. Many countries have made notable progress in increasing access to antiretroviral therapy and prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Response to gender-based violence in humanitarian settings requires services and support to prevent and protect affected populations, to reduce harmful consequences and prevent further injury, trauma, harm and suffering. United Nations guidelines for addressing the problem emphasize that all “humanitarian personnel ought to assume gender-based violence is occurring and threatening affected populations; treat it as a serious and life-threatening problem; and take actions…regardless of the presence or absence of concrete evidence” (IASC, 2005).

Gender-based violence includes sexual violence, including rape, sexual abuse, sexual exploitation and forced prostitution; domestic violence; forced and early marriage; harmful traditional practices such as female genital mutilation, honour crimes and widow inheritance; and trafficking (IAWG, 2010). Thus, in humanitarian settings, response to gender-based violence requires a multi-sectoral approach.

Protecting adolescents’ right to health

Humanitarian settings are accompanied by inherent risks that increase adolescents’ vulnerability to violence, poverty, separation from families, sexual abuse and exploitation. Moreover, childbearing risks are compounded for adolescents, due to increased exposure to forced sex, increased risk-taking and reduced availability of, and sensitivity to, adolescent sexual and reproductive health services.

Young people can be agents of positive change, capable of advancing reconstruction and development in their communities. But to be engaged in the process, they need access to an array of programmes including formal and non-formal education, life skills, literacy, numeracy, vocational training and innovative strategies to address insecurity and staff shortages.

Preventing and addressing gender-based violence

The attention to gender-based violence has grown from a focus primarily on rape to include early and forced marriage, domestic violence, female genital mutilation, and trafficking.

Local women are usually the first to respond and the first to find solutions, sometimes simple ones that can make the difference between life and death. When an earthquake rocked Haiti in 2010, the incidence of rape increased markedly, as the institutions that might normally protect them collapsed, women mobilized within displacement camps to protect each other and support survivors. The non-governmental organizations MADRE and KOFAVIV distributed whistles to women in displacement camps, which helped reduce the incidence of rape by 80 per cent in one camp. The installation of lights powered by solar batteries also contributed to a reduction in gender-based violence in the camps.

Women themselves also took the lead in the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan by forming watch groups and “women-friendly spaces” to protect themselves from gender-based violence. In July 2014, when another typhoon was forecast to strike the country, women dispatched watch groups to evacuation centres in coordination with female police officers and local authorities.

"I feel unsafe when I go to the bush because there are often men who rape women."

Photo © Panos Pictures/Chris de Bode

Resilience

Prevention, preparedness

and empowerment

A conflict or disaster can erase in a moment a generation of economic and social gains.

It can also permanently undermine an individual’s prospects for a better life, shattering opportunities and limiting choices.

And it can exacerbate existing inequalities in society, resulting in even greater hardship for the poor and marginalized, exacting a disproportionate toll on women and young people, particularly under the age of 20, who constitute about half the population in many conflict and post-conflict settings.

The profound human impact of disasters and conflicts on people, communities, institutions and nations highlights the critical importance of building resilience so all may better withstand the effects of crises and recover from them more quickly. Building resilience can also help mitigate the potential negative effects on the sexual and reproductive health of women and adolescent girls.

Who lives, dies and recovers during or after a conflict or disaster depends in part on the policies, programmes and social, economic and political contexts prior to the crisis.

Pre-empting poverty and inequality

The socioeconomic and structural factors that determine the capacity of communities to be resilient are critical preconditions to the effect of a disaster or conflict and require unwavering attention by governments.

While resilience may be seen as an end state, it is also an ongoing process, requiring continuous efforts to address the socioeconomic and structural factors—poverty, harmful gender norms and even food insecurity—that can influence whether communities may withstand or recover from a crisis or shock. Resilience-building as a process must be prioritized at every level and guided by local adaptation strategies, culture, heritage and knowledge. This requires the involvement of actors across the humanitarian and development continuum, but the process must be owned by the community.

Humanitarian emergencies, such as natural disasters and conflicts, can lead to a broadening and deepening of poverty and inequality. Resilience can mitigate those effects.

Building resilience involves addressing underlying causes of vulnerability, such as poverty and inequity, and initiating pre-emptive measures to build positive adaptation before a crisis strikes. Investments in reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health, and reproductive rights will protect those most affected by disasters.

which was destroyed when a 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Nepal in April 2015.

Photo © Panos Pictures/Vlad Sokhin

Lack of Coping Capacity, 2015

This dimension measures the lack of resources available that can help people cope withhazardous events. It is made up of two categories—institutions and infrastructure. This map shows details for the 12 countries with the highest values in the lack of coping capacity dimension.

Disaster risk reduction

Disaster risk reduction is a critical element in resilience. While humanitarian response is a short-term intervention, disaster risk reduction is a long-term undertaking that addresses the root causes of vulnerability during a crisis. Though some crises, such as earthquakes and tsunamis, cannot be prevented, their impact can be mitigated by pre-crisis investment in the building of sexual and reproductive health systems that are resilient and focused on the needs of the most vulnerable segments of the community.

Women, girls and resilience

One of the weakest areas of resilience currently is among women and girls, and the institutions that serve them. As long as inequality and inequitable access short-circuit their rights, abilities and opportunities, women and girls will remain among those most in need of humanitarian assistance and least equipped to contribute to recovery or resilience.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights are a cornerstone of young people’s transition to adulthood. When governments take steps to ensure the transition is safe and healthy, they are also taking steps to boost the “shock-absorbing” capacities of communities and nations, thereby creating environments where individuals can also become resilient.

People displaced by Typhoon Haiyan, Tacloban, the Philippines.

Photo © Panos Pictures/Andrew McConnell

Inclusive, equitable development

Development that is inclusive, equitable and that respects and protects everyone’s human rights, including reproductive rights and the right to health, including sexual and reproductive health, is central to resilience. The principles of inclusiveness, equity and rights are also the foundation for the new generation of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which will guide the international community in navigating the economic and social challenges of the coming 15 years.

Guaranteeing the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women and adolescent girls will go a long way towards achieving the goal of inclusive, equitable development, and can lead to more resilient societies, more capable of withstanding crises and rebuilding in ways that lead to even greater resilience.

But the new vision for sustainable development for the coming 15 years may only be realized if all of the world’s people are engaged and have a stake in its success. This means that women and adolescent girls must play a central role in leading and contributing to efforts to improve health and sustainable development at all levels—household, community, institutional and government—and not be left behind or relegated to a secondary role.

Moving Forward

A new vision for

humanitarian action

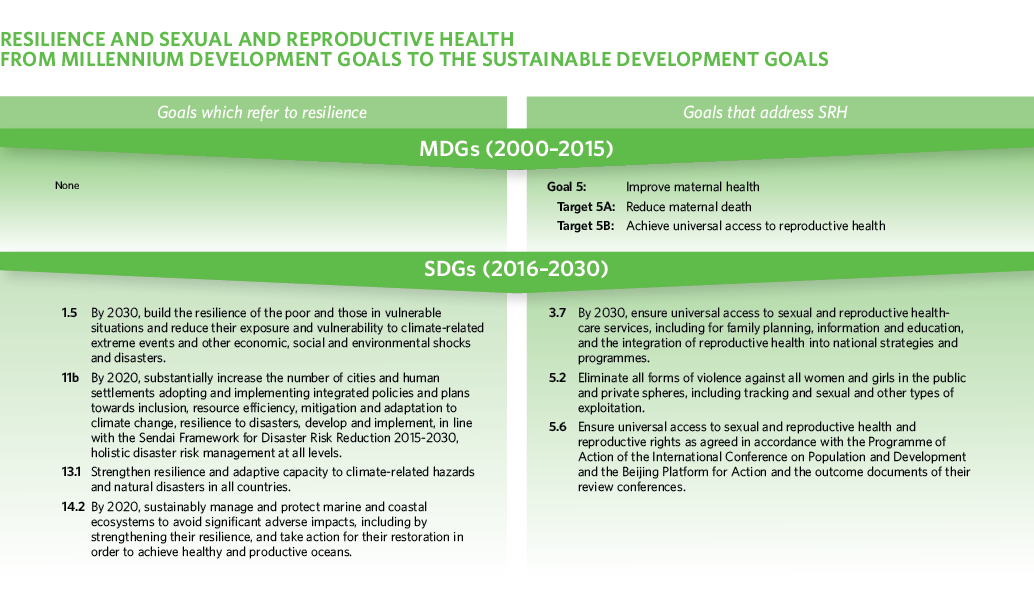

Tip the balance from reaction to preparedness and resilience

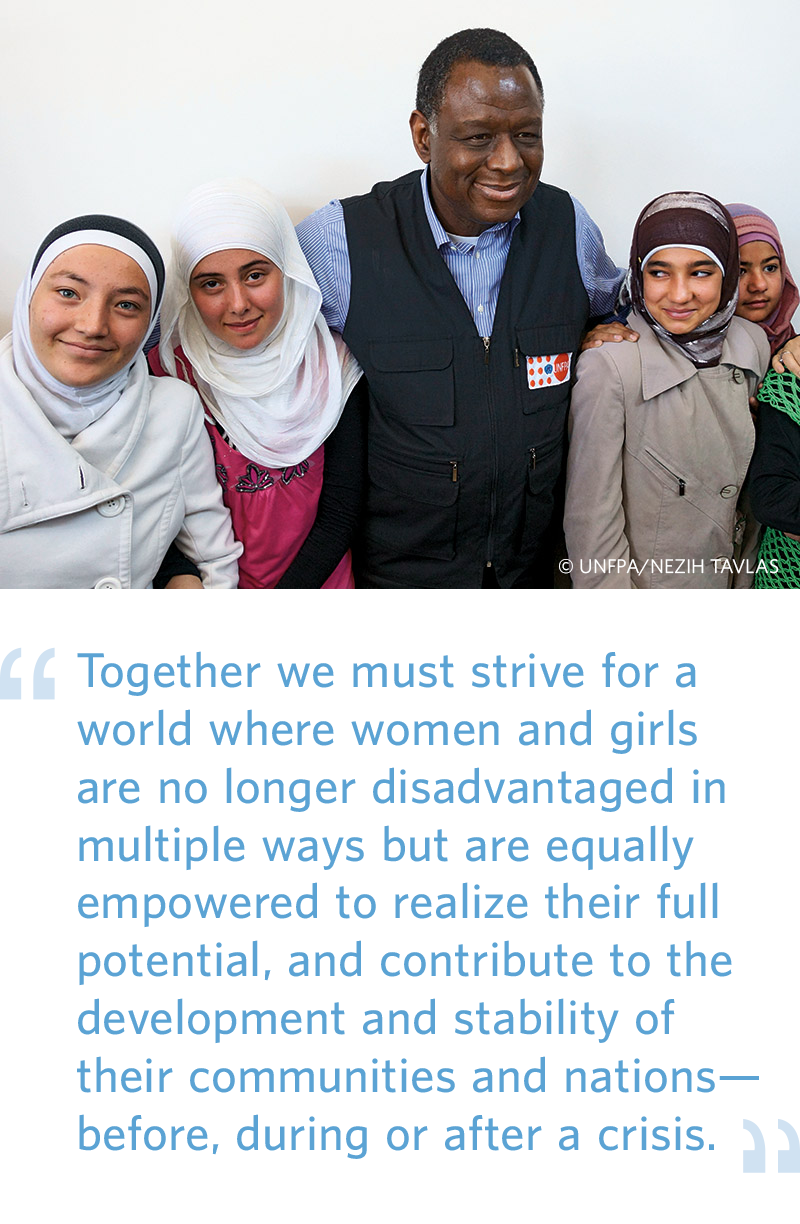

We must aim for a more resilient, less vulnerable world. Such a world would be one where development, within and across countries, is fully inclusive and equitable, and upholds all rights for all people. Where women and girls are no longer disadvantaged in multiple ways but are equally empowered to realize their full potential, and contribute to the development and stability of their communities and nations.

It would be a world where every country can manage its economy and its polity to guarantee everyone’s access to decent work and high quality essential services, including sexual and reproductive health care. Among those who set the course of public policies, there would be a sound understanding that investment in equitable, inclusive development is about the best and certainly the fairest and most humane investment that can be made. Far-reaching benefits include reducing the risks and impacts of crisis.

Better management of risk

Transformation to a more resilient, less vulnerable world also depends on better management of risks and institutions with sufficient capacities in place long before a crisis strikes. Risks first need to be comprehensively understood; only then can effective investments be made in measures to reduce them.

For those risks not fully avoidable, proactive preparation is critical to limit the worst consequences. One of the most central strategies in reducing risks in all countries is making sure people are resilient in the face of them. Those who are healthy, educated, have adequate income and enjoy all human rights have far better prospects when risks become reality.

UNFPA Executive Director

Promote equality

Transformation can begin, in part, in the aftermath of a crisis, but that largely depends on the response. If it mainly replicates existing discriminatory patterns, such as by failing to provide quality sexual and reproductive health services from the first moments, it is not transformative. It will fail as well on all scores of effectiveness and human rights. All humanitarian issues involve some kind of gender perspective, because men and women, girls and boys experience the world in markedly different ways. All types of humanitarian action therefore need to recognize and respond to these differences, and actively correct any disparities.

Wherever feasible, humanitarian assistance can challenge existing forms of discrimination, such as through providing comprehensive services for survivors of gender-based violence. It can enlist men and boys in building acceptance of new social norms, such as around women’s inherent rights and the peaceful resolution of differences.

A new vision for humanitarian action

reproductive

health and

rights

preparedness

inclusive

development

response

Tear down the divide between humanitarian action and development

The distinction between humanitarian response and development today is a false one. Humanitarian action can lay the foundations for long-term development. Development that benefits all, enabling everyone to enjoy their rights, including reproductive rights, can help individuals, institutions and communities withstand crisis. It can also help accelerate recovery.

Equitable, inclusive and rights-based development, and the resilience fostered by it, can in many cases obviate the need for humanitarian interventions.